Title: Timbuktu to Ouagadougou

Dates: 6th – 14th Dec GPS:

Distance: 445km Total Distance: 3558km

Roads: 200km gravel, 245km tarmac

Weather: Cooler nights, daily temperatures – low 30’s

This last section started with a two day journey on a pirogue up the River Niger from Timbuktu to Mopti rejoining the cycling line at Sevare, then pushing on to the Dogon Country where we stayed in a village called Djiguibombo (pronounced Jiggiboombo). From there I cycled across the border into Burkina Faso, staying in the town of Ouahigouya before a final 190km monster day into Ouagadougou!

A visit to Timbuktu would not be complete without visiting the library, mosque and markets. In keeping with the same themes of importance as Oualata and Djenne, Timbuktu exists as a centre for Saharan trade. The Touareg (people of the desert) settled at Timbuktu as it is well placed at the most northerly point of the River Niger, where it flows through desert sands. Here desert traders can meet river traders. Camping beside the river the first settlers noticed they suffered much illness, so Timbuktu is set 18km north of the river in the dry desert sands. To find out more click on link: Timbuktu’s wonderful history.

The library benefits from contributions worldwide. Compared to Oualata, the main library is beautifully kept; the manuscripts well displayed and protected in a climate controlled atmosphere away from direct light in glass cabinets. Great efforts are being made to preserve manuscripts some of which are up to 1000 years old. One of the more interesting books I thought was a 16th century manuscript outlining the rights of Islamic women – that all Islamic women have the right to spend time to make themselves more beautiful. The world’s oldest book is also on display. They don’t really know it’s age but it was rediscovered in the 11th Century. It had been stolen by the Moroccans many years before and buried underground. Timbuktu attracted some of the greatest scholars of the day, and so many manuscripts were written there as well as brought over the desert from as far away as Iraq and the Middle East. I started to wonder about whether there could be some sort of partnership formed with Oualata to preserve their treasures. I understand that the doors are open for anyone from Oualata to visit and learn about how to catalogue and preserve their books, but they need to approach Timbuktu.

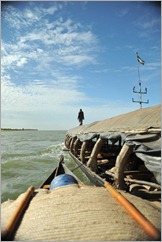

Paddy and I took a pirogue back down from Timbuktu to Mopti. Paddy had been ill so we were quarantined on the pirogue which was towed beside a larger public pinnace. John and Dan drove the vehicle back to Sevare. This was an opportunity to take a different look at life on the river and how all those who live near it rely on the Niger for everything; food, transport, water… The river is massive, often a kilometre or two wide. About 100km north of Mopti the waters disperse into Lake Beda where the normally calm waters became a little choppy. Next we entered a sea of reeds which normally lined the banks. The boats cut through a maze of channels through which we wondered how the captain navigated at night.

Paddy and I took a pirogue back down from Timbuktu to Mopti. Paddy had been ill so we were quarantined on the pirogue which was towed beside a larger public pinnace. John and Dan drove the vehicle back to Sevare. This was an opportunity to take a different look at life on the river and how all those who live near it rely on the Niger for everything; food, transport, water… The river is massive, often a kilometre or two wide. About 100km north of Mopti the waters disperse into Lake Beda where the normally calm waters became a little choppy. Next we entered a sea of reeds which normally lined the banks. The boats cut through a maze of channels through which we wondered how the captain navigated at night.

The only downside of the two day trip was that I ended up with another gastro after being served the same sauce for three meals. I was over the worst of it quickly but it did have a lasting effect for another week or so, until after Ouagadougou.

John had to do some work on the vehicle which meant we did not set out from Sevare until 3pm the following day. Our destination was the Dogon Country, Mali’s biggest tourism draw card. We knocked off the first 60km to Bandiagara in daylight. The next 21km however to Djiguibombo was in the dark; Dan and I cycling on our own for the first ten, feeling a little vulnerable without light in a strange place. Djiguibombo is set at the top of the Falaise de Bandiagara (cliff face which extends 150km, all the way up to Douentza which we visited en route to Timbuktu). It was a wonderful sight overlooking the tipi-like thatched rooftops and labyrinth of mud-walled houses in the early morning light. Dan and I coasted down to the bottom of the falaise on a spectacular 9km ride to Kani Kombole where we left our bikes and vehicle for a two day diversion on foot with our Dogon guide, Moumimi (Momo). This was the final stage of looking at the cultures of the Niger River region. Two days is just long enough to get a taste of the complex and elaborate culture. To really do it justice you could easily spend a week or two walking all the way to Douentza.

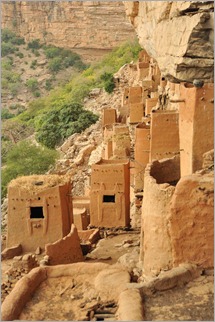

Passing a rather beautiful little mosque (mini Djenne architecture) Momo explained that Islam and Christianity (late comers in the scheme of Dogon history) co-exist with more traditional Dogon animism. Everyone respects each others’ religion bit they do not intermarry. We made a simple 4km walk to Teli. From a distance we could see a series of boxes and dwellings built into the cliff. After lunch we climbed up to explore. The boxes were an extensive series of  granary stores. Most grains these days are stored in the village at ground level and these elevated stores are only used to hold millet, sorghum and beans after a very good year. Built into the rock and in higher positions were tiny houses. Momo described these people as pygmies; the guide book calls them the Tellem people. These were the original inhabitants who lived off the fruits of the forest below. Living high up would have given them a great vantage point to defend themselves and stay safe from large predators. The Dogon believed that the Tellem could fly and had magic powers to reach them. The Tellem also used to bury the dead in their little houses. It seems more plausible that the climate a few hundred years ago was wetter and the Tellem used overhanging vines to climb to their houses. The Dogon and Bozo people arrived in the region roughly 300 years ago. The Bozo are the traditional fishermen who chose to inhabit the banks of the Niger (and still do). The Dogon arrived in the region and pushed out the Tellem so they retreated east. The Dogon cut down the forest for firewood, cultivated fields and raised animals. They basically destroyed the Tellem habitat so they could find nothing to eat. From high up the landscape is typically dry and bare and studded by regular, compact villages. Up in the cliff is the home of the Hogon, the spiritual leader. The Teli Hogon died about ten years ago. Aparently they have chosen a new one, but he is not yet ready to assume the mantle. Hogons are usually old wise men.

granary stores. Most grains these days are stored in the village at ground level and these elevated stores are only used to hold millet, sorghum and beans after a very good year. Built into the rock and in higher positions were tiny houses. Momo described these people as pygmies; the guide book calls them the Tellem people. These were the original inhabitants who lived off the fruits of the forest below. Living high up would have given them a great vantage point to defend themselves and stay safe from large predators. The Dogon believed that the Tellem could fly and had magic powers to reach them. The Tellem also used to bury the dead in their little houses. It seems more plausible that the climate a few hundred years ago was wetter and the Tellem used overhanging vines to climb to their houses. The Dogon and Bozo people arrived in the region roughly 300 years ago. The Bozo are the traditional fishermen who chose to inhabit the banks of the Niger (and still do). The Dogon arrived in the region and pushed out the Tellem so they retreated east. The Dogon cut down the forest for firewood, cultivated fields and raised animals. They basically destroyed the Tellem habitat so they could find nothing to eat. From high up the landscape is typically dry and bare and studded by regular, compact villages. Up in the cliff is the home of the Hogon, the spiritual leader. The Teli Hogon died about ten years ago. Aparently they have chosen a new one, but he is not yet ready to assume the mantle. Hogons are usually old wise men.

We walked on to Ende, Momo’s home town (population approximately 3000) where we stopped for the night. Ende has similar architecture set in the cliff face above the town. On day two we put in a decent distance; walking along the base of the escarpment, then climbed a natural chasm to Begnimato at the top. Compared to the kind of day I’d usually put in on the bike, walking 20-odd kilometres was a doddle on the cardiovascular side, but feet and knees, especially on the downhill, weren’t used to it. The slope was lush and green with overhanging vines and ficus trees. Views from the head of the chasm were spectacular. Begnimato’s setting amongst the rocks, with three individual villages (animist, Christian, Muslim) was special. After a long lunch break we started to make our way back, along the top of the escarpment to Indelou, the most amazing village we visited, then via a series of steps and laddersdown another chasm. Indelou was animist only – there was no mosque. I had the impression that of the villages we had seen, this was the most pristine – most like the original Dogon culture. In Begnimato and Indelou you can see how people use the rooves of their houses to store much of their food. It makes for an interesting and colourful patchwork.

Over the last couple of weeks we have visited Mali’s trifecta of World Heritage sites; Djenne, Timbuktu and the Dogon Country. The region is probably West Africa’s biggest attraction and the fact that they are in reasonable proximity means tourism is the major source of income. Timbuktu is obviously being hit by the security alert and the fact that the French have pulled their expats from the area. I felt tourism is being managed reasonably (I have seen much worse management). All walkers pretty much travel with a Dogon guide to get the best of the region. This is also a safeguard that groups remain small and the paths were not full of litter. Each visitor also pays a tourist tax for every village they explore so that this can help them preserve their heritage and sustain their income. Djenne also had better infrastructure, such as drains and ongoing maintenance of the mosque and streets.

The following day we said goodbye to Momo and set off towards Bankass, Koro and the Burkina Faso border. After about 40km, Dan could cycle no longer; his knee had become sore on the ride into Djiguibombo. He had kept it pretty quiet hoping he could work through it, but for quite some time he had been basically cycling with one leg. I cycled on alone – 162km that day on gravel road, all the way to Ouahigouya, then 189km the following day to reach Ouagadougou. I had to keep my wits about me and find a little more in my tired legs to negotiate peak hour traffic entering the city. Two crazy days, but it did allow us to catch up a day and give more time to organise the next complicated stages of the journey.

Of all the African cities so far, Ouagadougou seems a bit more low key and better organised. There are even cycle/motorcycle lanes which allow the traffic to flow a little better. There somehow seemed to be less pressure, yet nothing particularly remarkable to see.

In Ouagadougou we have been looked after so very well by Gryphon Minerals, one of our mining sponsors. A special thank you must go to Isabelle, Pascal, Alice and Martin for taking care of us.

Next we’re heading to Kaya and the Samentenga region north east of Ouagadougou to visit a couple of Plan International projects, concentrating on education, and in particular girls’ education.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

KATE AND TEAM

Merry Xmas and happy new year from Kangaroo Valley where it has rained for 24 hours.

Congratulations on your progress in 2009 now 2010

Cheers Mike