Title: Yaounde, Cameroon to Mayoko, Republic of Congo

Dates: 2nd – 12th March GPS:

Distance: 1245km Total Distance: 9447km

Roads: 713km tarmac, 532km gravel, mud..., continuous steep hills

Weather: Extreme humidity, hot, thunderstorms

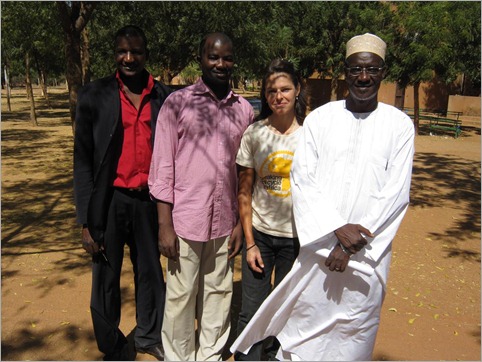

The ten days spent off the bike in Yaounde (and Bertoua) were important to recharge the batteries, organise visas for Gabon, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo and make a smooth transition within the team. John has gone home to Scotland for a couple of months and Simon Vernon has taken over in the driver’s seat. It was great to have a terrific place courtesy of Sundance Resources, to make the pit stop. We also had an opportunity to meet and spend some time with Nerice Kihkwi, who has been such a great help organising out all sorts of things for us during our five weeks in Cameroon, such as visas, visa extensions, contacts, guides and she is a wealth of information. (If anyone is planning to visit Cameroon I fully recommend getting in touch with Nerice. Her company is Nixon Travel – nerice80@yahoo.fr, +237 22075055)

It took a while to regain my cycling legs after such a long stint off the bike. I was pretty tired and dehydrated when I arrived in Yaounde, but on leaving I was refreshed and feeling much stronger. This phase through Gabon was to require an intense, demanding effort, so I needed to be up for it. We returned to the exact spot where I stopped cycling, just outside of Yaounde, and set off. It took just two days to reach the Cameroon/Gabon border village; nearly 300km from Yaounde. The road quality was excellent although the humidity and undulations were a bit of a test. On the whole it was pretty straight forward, which allowed the new team combination to become settled. Now that the roads are flanked by thick forest it is more difficult to find appropriate rest stops and campsites. The region in general looked more developed – bigger houses with more satellite dishes, educated young men wanting to make good conversation and better facilities overall.

On the second day out we had a couple of dramas. We managed to lose each other, which you would think would be difficult to do on a straight highway. On the last town before the border, I received some confusing instructions by the man at the toll post, who sent me back into the town of Ambam to get my passport stamped. The guys I thought must also be in the town so I retraced a few kilometres but could not find them or the right place for immigration. I was sent on a wild goose chase and eventually found the Marie (mayor’s office) who directed me to the police station. A very kind fellow guided me on his motorbike. First he had to remove his recent catch of bushmeat – a monkey and a wild dog – which was draped over his back carrier! The police sent me back to where I started and then a further 25km to the border. Meanwhile the guys had gone straight through the town and were wondering where I was, getting worried. They’d been up to the border town and back before we reconnected. I had done an extra 10km in the process which was frustrating, but at least no harm was done. We reached the customs post by nightfall, just as the clouds burst. The customs officials allowed us to stay beside their building, so we had a secure place for the vehicle.

While all of this was going on, my middle chain wheel wore out and so by the end of the day the cog could not support the chain. This meant that every time I put any pressure on the chain, it would slip, so I had to use either the big cog or the granny gear to cycle. As soon as we stopped for the night Dan swung into action, removing the middle chain wheel from the spare bike to fix the problem. I was hoping that the drive train would last until after the next few weeks when we are likely to have some bad, wet roads.

There were many check posts to cross over into Gabon, which took some time, but there were no problems for us entering the country. The roads were in excellent condition, but the going was tough – continuous hills with some very steep gradients and humidity extreme.

Gabon has one of the highest GDP’s of any country in Africa (per capita income is almost $US15,000) mostly due to a thriving oil industry along with other primary exports such as logging, manganese and uranium. Since independence in 1960, Gabon has had a stable government – in fact Omar Bongo was the only president the country had known until he died and passed his reign on to his son Ali Bongo. A single party democracy? I’m not sure how this one works. Regarding GDP, the figures are really skewed because there is an uneven wealth distribution. 20% of the people receive 90% of the income while about one third live in poverty. The population of Gabon is only about 1.5 million which is a more manageable number of people to deal with.

Initial impressions as I cycled through the countryside: some quite grand houses, a lot of construction too, the standard of cars was high (rarely saw the usual African bombs held together with tape and overloaded), maintained gardens, sparse population density (in Cameroon there were always people around). Some unusual wealth indicators I noticed – less rubbish around, people were cutting grass with ‘Whipper Snippers’ rather than by hand with machetes and there were many dogs! Cyclists are usually very vulnerable to dogs if they decide to chase and nip at ankles. For the whole of West Africa, the dogs have been just one breed and poorly treated; battered, abused and not revered as man’s best friend. Arriving in Gabon I was suddenly being lined up and ambushed regularly by dogs (a range of breeds too) who would chase me out of their territory to protect their owners. Gabonese obviously treat their dogs as pets – I think this is another sign of wealth, although you won’t find in any of the economic indicators.

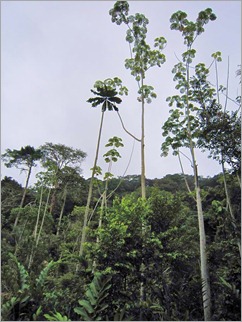

I saw little agriculture – there were regular pockets of slash and burn zones – some recently cleared, others where forest was regenerating. Despite having soil and growing conditions which could produce anything, Gabon relies on importing just about everything such as fresh produce from Cameroon and goods from France. In Gabon and surrounding countries there is a heavy reliance on food from the forest, including bush meat. Bush meat means basically any wild animal with a heart beat including; monkeys, gorillas, chimpanzees, elephants, gazelles, lizards, snakes, porcupines, wild pigs (which they call porky pig!). It is a very controversial practice. They have always done it, but when the practice is combined with loss of habitat from development, logging and increasing populations, extinction of some species is a real prospect – the most well-known and emotive issues being with our closest relatives such as chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos.

We followed the main road all the way to Alembe, just over the Equator. Crossing the Equator was a real landmark – I feel closer to home now we’re in the Southern Hemisphere! I had been prepared for some bad road, but it had all been recently sealed with some magnificent road building – just continuous 10% gradients and serious heat to contend with. I’ve developed some very uncomfortable heat rashes and the anti-malarial medication I started to take in Yaounde has reacted badly with me. While we benefitted from the good roads, apparently the government has been overspending. As Gabon’s oil fields are now on the decline and borrowing has increased, there are worries for the future economy here.

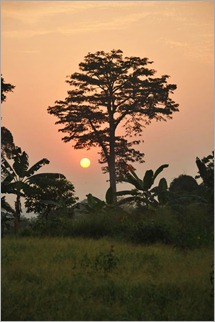

Just as we turned off the main road and over the Okano River bridge heading in the Franceville direction, some local foresters stopped to warn us about travelling through the Lope National Park which was on our route because on the panthers, elephants and buffalo. The road actually skirts the park perimeter and while we decided that the vehicle should travel basically on my tail through there, we had no trouble. In fact we didn’t see an animal! As usual, travelling on rough dirt roads really changes the ambience of the location. The first day was really tough going. At the start I had to ride through a heavy rainstorm. It took eight hours to do 105km at just over 13km per hour because the descents were so rough and steep that I had to travel almost as slowly downhill as I did up to keep control of the bike. It was a bit claustrophobic pushing through the forest, but around the magnificent Ogooue River there were clearings and a couple of small villages. Once in the Lope NP, the land was open and the road a better quality. We decided to treat ourselves as we had just done 6 days of camping. There was a lodge nestled in a bend in the river complete with mown lawns and an airport nearby.

Just as we turned off the main road and over the Okano River bridge heading in the Franceville direction, some local foresters stopped to warn us about travelling through the Lope National Park which was on our route because on the panthers, elephants and buffalo. The road actually skirts the park perimeter and while we decided that the vehicle should travel basically on my tail through there, we had no trouble. In fact we didn’t see an animal! As usual, travelling on rough dirt roads really changes the ambience of the location. The first day was really tough going. At the start I had to ride through a heavy rainstorm. It took eight hours to do 105km at just over 13km per hour because the descents were so rough and steep that I had to travel almost as slowly downhill as I did up to keep control of the bike. It was a bit claustrophobic pushing through the forest, but around the magnificent Ogooue River there were clearings and a couple of small villages. Once in the Lope NP, the land was open and the road a better quality. We decided to treat ourselves as we had just done 6 days of camping. There was a lodge nestled in a bend in the river complete with mown lawns and an airport nearby.

One of the most unpleasant annoyances we are having is with sweat bees and normal bees. If we stop anywhere in the rainforest it takes about ten minutes for them to pick up on our scent. Sweat bees are like tiny black flies. They don’t bite, just crawl in your ears, hair, eyes, down your shirt – everywhere in their thousands. None of us have experienced anything like it. Lunch breaks have been very quick and there is no opportunity to rest. They disappear at night, but setting up camp after our Lope stay, and then at first light the morning, we were driven basically mad – totally incapacitated by not just sweat bees but normal bees too. I think we were all stung – but mostly managed to pull out the stings.

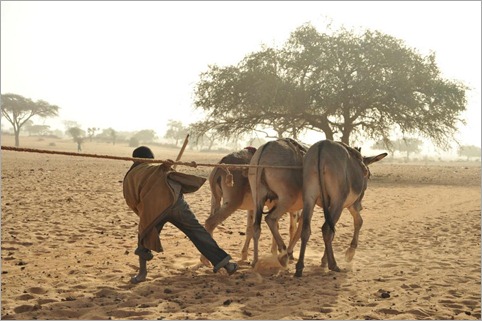

We continued to Lastoursville (and 12km of tarmac) – it rained most of the day, so there was again little stopping. I was covered in mud, but at least it was not cold. From Lastoursville, the going was very slow and tough, but fortunately it was dry (or the road would have been impossible in places). For much of the way there was a lot of road building going on by the Chinese. As in many parts of Africa, the Chinese are building infrastructure in exchange for natural resources.

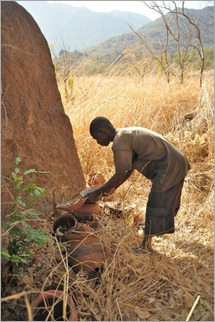

We had been doing so well it looked as though we would reach Mayoko across the Republic of Congo border a day ahead of schedule as long as I could put in a huge day to get there. We were up very early and I was on the road before 7am. There was about 30km of tarmac into and out of Moanda, a major town in the district. Then things started to deteriorate. More of the same as before – but even bigger, steeper hills with huge channels and washouts. I struggled into the border town of Bakoumba where we had to have our passports stamped and Simon had customs to deal with.  Then the rains came which changed everything, rendering the piste to thick sticky clay which caked my tyres and drive train so that I could not turn the wheels. In some cases I just had to carry the bike uphill because I could not get up enough speed to flick the mud off. At times I could only go a few metres before stopping to scrape out the mud. Dan was there to help when the vehicle was close. It looked as though we would at least make the border town of Mbinda, 25km from Mayoko at last light, but as we crossed the range another thunderstorm erupted and I managed about 500m in half an hour. We decided to stop and return to a tiny hamlet we had passed two kilometres before. They offered us shelter for the night, so at least we were warm and dry. The following morning we reached the border post which was just 2km further on, but the gate was locked and no one seemed to be around. Eventually we spoke to a woman and her husband was able to process our passports, but as no one really used this crossing he had to phone to Mbinda and have someone ride out on a motorbike with the key to unlock the gate to let the vehicle through. Meanwhile Dan had cooked porridge for breakfast. I set off first – the road was shocking with many muddy slopes and washouts. The road to Mayoko was slightly better as it started to dry out. We arrived for lunch the next day.

Then the rains came which changed everything, rendering the piste to thick sticky clay which caked my tyres and drive train so that I could not turn the wheels. In some cases I just had to carry the bike uphill because I could not get up enough speed to flick the mud off. At times I could only go a few metres before stopping to scrape out the mud. Dan was there to help when the vehicle was close. It looked as though we would at least make the border town of Mbinda, 25km from Mayoko at last light, but as we crossed the range another thunderstorm erupted and I managed about 500m in half an hour. We decided to stop and return to a tiny hamlet we had passed two kilometres before. They offered us shelter for the night, so at least we were warm and dry. The following morning we reached the border post which was just 2km further on, but the gate was locked and no one seemed to be around. Eventually we spoke to a woman and her husband was able to process our passports, but as no one really used this crossing he had to phone to Mbinda and have someone ride out on a motorbike with the key to unlock the gate to let the vehicle through. Meanwhile Dan had cooked porridge for breakfast. I set off first – the road was shocking with many muddy slopes and washouts. The road to Mayoko was slightly better as it started to dry out. We arrived for lunch the next day.

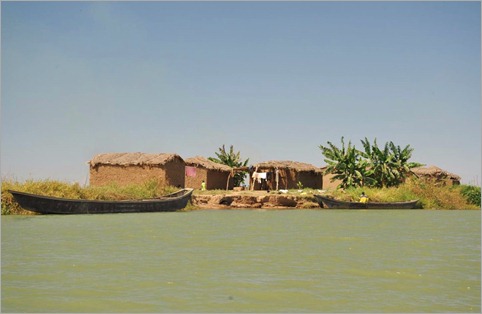

The prime reason for choosing this unusual route across the Gabon-ROC border (rather than down the main road) was to link up with another of our sponsors, DMC Mining who are exploring the iron ore reserves in the region. Not only is it great to have a good place to rest, but it is an opportunity to see a part of Africa few get to see. The ROC is recovering from ten years of brutal civil war (1987-97). As far as development goes, war negates everything to ground zero. So far we have seen evidence of many grand developments; mining industries, a narrow gauge railway line which runs to Point Noir the major port on the Atlantic coast, colonial buildings, an overhead conveyor system; pylons and wires now overgrown in the jungle. All the forest is secondary regeneration. There are no large trees as it was once clear felled. On our day off, the DMC staff arranged for us to tour the region. They have also arranged security for us to guarantee our safety. First stop on the tour was in the village to collect the mayor’s representative, chief of police and an armed police escort (including a police woman). Simon drove the Land Rover, following a DMC utility through the forest.

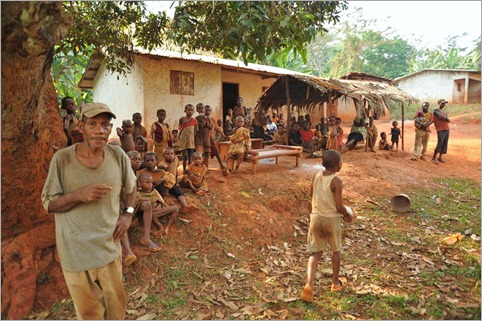

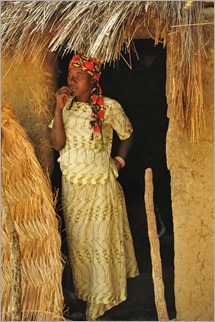

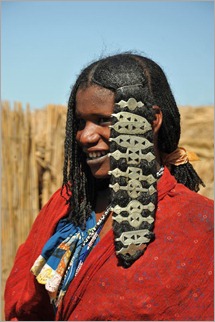

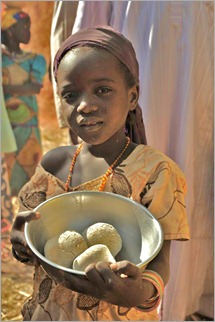

First stop was an emotive visit to the last pygmy village in the Mayoko region, Loussoukou. I’d asked if we could learn more about the local cultures, and thought it would be a good follow up to compare their situation with that of the Baka in Cameroon. There are just 37 people left in the village (and a few more kids I think!). That is all there are left of their group who have their own language (although they speak French and another language too). I tried to find out why they are disappearing as a group. The main reasons I can deduct are that some have integrated and moved away, the civil war, change of lifestyle which, like the Baka has resulted in loss of self esteem and alcohol issues, and loss of habitat due to deforestation (this would have occurred during colonial times and before the war).

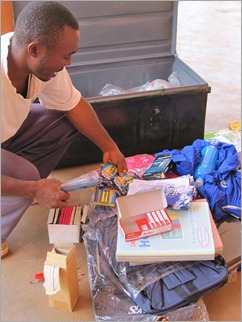

They knew we were coming and had prepared two letters for me pleading for help; the one from the chief of the village has an official stamp. Debi, our interpreter from DMC translated. It is grim reading. They can’t get any help – nothing from the government and the country is in such a state with poor infrastructure and corruption that it isn’t conducive for NGO’s to set up here yet. They do grow and produce things to sell, but they have no facilities. We moved over to the school. They have three teachers but can only afford to pay one with the money they earn. They have no learning materials. People are sick – malaria being the main killer – but they have no health facilities and usually have to treat problems with traditional medicines. They feel that they are really making a last ditch effort as a unique group of people. Again I felt so helpless. All I can do at this point is tell the world about it through this blog. They say they are not looking for a few gifts, but help which brings about long term changes; especially with regard to primary education and health. I can also help make a connection (via DMC) if anyone wishes to make a difference.

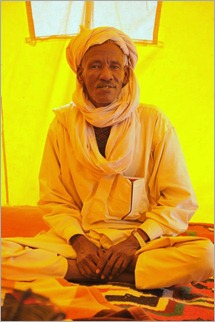

Our entourage moved on. Next was a courtesy call to the brother of the ex-president of the Republic of Congo, Mr Lissoube. Now 85, he might be a little frail but he is still the chief of his village. The former president was in charge of the country throughout the second half of the civil war, from 1992-97. Currently in exile in France, he apparently has good relations with the current president and is due to return to ROC soon.

Our entourage moved on. Next was a courtesy call to the brother of the ex-president of the Republic of Congo, Mr Lissoube. Now 85, he might be a little frail but he is still the chief of his village. The former president was in charge of the country throughout the second half of the civil war, from 1992-97. Currently in exile in France, he apparently has good relations with the current president and is due to return to ROC soon.

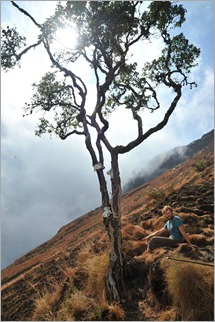

The finale for the day was a hike through the jungle to see a spectacular waterfall/set of rapids on the Louesse River. Our party traipsed through thick vegetation, the village leader with machete in hand. It was much longer than described – about an hour’s walk each way. Our police woman took time to collect some bush tucker on the way. We tried the two types of fruit which were different varieties of the Ntounde fruit. The flesh tasted like a cross between a lemon and passionfruit and was probably full of vitamin C. I made the mistake of crunching on the seeds, which were horribly bitter. Another villager picked what I think were wild plums, but they were so chalky that they were definitely an acquired taste!

That night Simon noticed his chest was covered in spots. He was experiencing cold sweats and felt feverish. At first the doctor though it an allergic reaction to a bite, but then he tested positive to malaria when we checked with a self-testing kit. This morning, after taking that treatment, he seems much better, but we decided to stay another day to make sure he is alright. We’ll never be 100% sure it was malaria, but the key to treating malaria is early detection and treatment, which we have certainly done.

Tomorrow we set off for a 660km stint to Brazzaville. Our progress is really dependent on the rain. If the road is dry, I can get there in 5-6 days (mostly dirt roads). We are under pressure to get our Angolan visas which are the most difficult to get (for more than 5 days) of any country in Africa. Hopefully we have enough connections in the right places and cannot do any more than we have done about it at this stage.

{ 2 comments }