Title: Mayange Millennium Village, Kigali and the Genocide

Dates: June 9th and 10th GPS:

Distance: 0km Total Distance: 17,068km

There are so many complex issues to write about that it is impossible to squeeze them all into one blog. The easiest news to describe is that it is great to have Zdenek back. He returned to the expedition, flying in from Europe on the 9th. In Kigali we stayed at the One Love Guesthouse, part of a self-funding effort for the One Love Project. Profits from the guesthouse, restaurant and bar go towards developing and maintaining orthopaedic workshops in Kigali and Bujumbura (Burundi) which have so far supplied over 6000 prostheses, orthoses, sticks or wheelchairs to those handicapped by the 1994 genocide. We were fortunate to meet Emmanuel, the founder and driver of the project along with his Japanese wife Mami and son. Emmanuel spent time showing us around and explaining about his vision and the organisation.

There are so many complex issues to write about that it is impossible to squeeze them all into one blog. The easiest news to describe is that it is great to have Zdenek back. He returned to the expedition, flying in from Europe on the 9th. In Kigali we stayed at the One Love Guesthouse, part of a self-funding effort for the One Love Project. Profits from the guesthouse, restaurant and bar go towards developing and maintaining orthopaedic workshops in Kigali and Bujumbura (Burundi) which have so far supplied over 6000 prostheses, orthoses, sticks or wheelchairs to those handicapped by the 1994 genocide. We were fortunate to meet Emmanuel, the founder and driver of the project along with his Japanese wife Mami and son. Emmanuel spent time showing us around and explaining about his vision and the organisation.

Emmanuel was himself handicapped as a youngster after an injection during a medical procedure went wrong. He experienced all the difficulties of being handicapped in a society with no facilities or support to accommodate his disability – he is a survivor who had to struggle physically and mentally to be independent.

Emmanuel was himself handicapped as a youngster after an injection during a medical procedure went wrong. He experienced all the difficulties of being handicapped in a society with no facilities or support to accommodate his disability – he is a survivor who had to struggle physically and mentally to be independent.

Emmanuel first had the idea of creating the orthopaedic workshops in 1989, just before the first conflict in 1990. Even then he was a skilled networker. He made contact with a Japanese man who later invited him to Japan to study, complete his tertiary education and learn skills needed to realise his idea of setting up the workshop. As a Tutsi, he was imprisoned and tortured during the early 90s. The One Love Project was established in 1996 in order to support handicapped people to become independent in society. The workshops were opened in Kigali in 1997 and Burundi in 2007.

One Love is now diversifying with warehouses in Miami and Kenya, where handicrafts made by handicapped artisans are sold; profits helping to fund the workshops so that beneficiaries receive their artificial limbs free of charge. The organisation also trains technicians, rehabilitates people with disability to rejoin society, has set up a vocational training school to teach all sorts of skills in business and handicrafts, encourages sports participation to those with disability, runs the guesthouse and restaurant (which provides employment to the handicapped) and many other activities which provide support.

One Love is now diversifying with warehouses in Miami and Kenya, where handicrafts made by handicapped artisans are sold; profits helping to fund the workshops so that beneficiaries receive their artificial limbs free of charge. The organisation also trains technicians, rehabilitates people with disability to rejoin society, has set up a vocational training school to teach all sorts of skills in business and handicrafts, encourages sports participation to those with disability, runs the guesthouse and restaurant (which provides employment to the handicapped) and many other activities which provide support.

Emmanuel gave us a tour of the workshop. He has sourced materials and equipment from all over the world – Japan, Switzerland, Germany, the US and the UK for example. He also managed the Rwandan team for the Sydney Olympics. It was a moving experience watching new prostheses being measured and shaped, knowing that each artificial limb was going to make a huge difference to someone who cannot afford it. Once receiving the limb the next challenge would be to learn how to use it and to reintegrate into the society where they would have previously been marginalised. To find out more please visit their website at OneLoveProject.org.

Emmanuel gave us a tour of the workshop. He has sourced materials and equipment from all over the world – Japan, Switzerland, Germany, the US and the UK for example. He also managed the Rwandan team for the Sydney Olympics. It was a moving experience watching new prostheses being measured and shaped, knowing that each artificial limb was going to make a huge difference to someone who cannot afford it. Once receiving the limb the next challenge would be to learn how to use it and to reintegrate into the society where they would have previously been marginalised. To find out more please visit their website at OneLoveProject.org.

The main focus of our journey through Rwanda was to visit and learn about the Mayange Millennium Village. Mayange is the third Millennium Village featured during the expedition – the others being Potou, Senegal and Tiby/Segou, Mali. Those following the expedition from the early days will recall that the purpose of the Millennium Village program across Africa is to implement strategies in villages located in selected vulnerable zones to ensure the Millennium Development Goals are achieved by 2015.

My original connection with the Millennium Village initiative came via Ericsson, one of our gold sponsors who is also a major supporter of the MVs. However since the Mali visit I have also developed a strong partnership with another of the key stakeholders, Millennium Promise who is based in New York. (Please check out the Partners’ page and click on the logos to learn more about both)

Potou and Tiby are both located in the Sahel region. A major reason as to why they are classified as vulnerable is because of their marginal, drought-prone climates with unreliable rainfall. In Mayange, water is still a major issue as it needs to be piped from a reservoir to producers over about 40km (which is expensive), but here the communities are particularly susceptible as they recover from the 1994 genocide.

After our meeting with Emmanuel we were a little late as we set off for Mayange, roughly 40km south of Kigali. Ever since arriving in Rwanda (from Tanzania), the ‘land of a thousand hills’ had been living up to its reputation – it had been an uninterrupted rollercoaster ride over some huge hills – but nearing Mayange, the land flattened out. We stopped in at the office headquarters where Deo gave us a tour of the Millennium Village nerve centre.

When the project was set up in 1996, just two years after the genocide there was no electricity in Mayange and so for practical purposes they had to set up offices in a larger village which had power. Donald Ndahiro, the director of the Mayange MV made time out of his busy schedule to give an overview of the initiatives. While each MV aims to achieve the MDGs by 2015 and there are many common directives, each community has specific issues and challenges to deal with to get there.

When the project was set up in 1996, just two years after the genocide there was no electricity in Mayange and so for practical purposes they had to set up offices in a larger village which had power. Donald Ndahiro, the director of the Mayange MV made time out of his busy schedule to give an overview of the initiatives. While each MV aims to achieve the MDGs by 2015 and there are many common directives, each community has specific issues and challenges to deal with to get there.

Donald outlined what his departments were doing to improve infrastructure and communications, education, farming and agriculture, health and trade/business. I asked whether he thought the initiatives were scalable and appropriate examples which could be adopted by the rest of the country. Donald said that the government had already recognised this and steps had been taken to include some of the strategies as national priority.

We then drove to Mayange where we met Jeanette who showed us around for the rest of the visit. The plan was to see at least one example of each of the main projects. Jeanette’s job involves liaising with the village committees and then communicating their ideas and needs to then report back to Donald and the team. The MV team then assess how a certain directive could fit in to the overall plan – to assist in realising the MDGs. Once a plan is approved, Jeanette would then present a proposal to the village leaders.

Donald mentioned that the MV project has already had much success in improving food security since 2006. Drought protection has been a major focus by increasing crop diversity, improving agricultural techniques and by developing business opportunities, particularly by facilitating the formation of farming cooperatives. Programs including: the artificial insemination of cattle, honey production, fishing, poultry and a cassava processing plant have all been introduced with a focus on skills transfer.

Jeanette took us to meet one of the most successful farmers who has really embraced everything he has been taught – and shown great initiative when new methods did not work first time around. The farmer was so proud of what he’d done in three years. We saw his field of pineapples, mango and avocado trees laden with fruit, bananas, sugar cane, maize, capsicums/peppers, onions, beans and tomatoes. He’d learned how to intercrop and plant nitrogen fixing plants to improve soil fertility. There were drainage channels dug and mulch spread around plants to reduce moisture loss and increase fertility. Everything looked amazingly healthy, including the dairy cows. The farmer could now afford to extend his house and strengthen the walls.

Jeanette took us to meet one of the most successful farmers who has really embraced everything he has been taught – and shown great initiative when new methods did not work first time around. The farmer was so proud of what he’d done in three years. We saw his field of pineapples, mango and avocado trees laden with fruit, bananas, sugar cane, maize, capsicums/peppers, onions, beans and tomatoes. He’d learned how to intercrop and plant nitrogen fixing plants to improve soil fertility. There were drainage channels dug and mulch spread around plants to reduce moisture loss and increase fertility. Everything looked amazingly healthy, including the dairy cows. The farmer could now afford to extend his house and strengthen the walls.

Next we paid a visit to one of the primary schools. More classrooms have been built and teachers provided to improve the student-teacher ratio. School meals are now provided; many of the vegetables are grown in a kitchen garden. Interestingly, in the garden I spotted a moringa tree (Remember this tree is native of the Sahel).

Next we paid a visit to one of the primary schools. More classrooms have been built and teachers provided to improve the student-teacher ratio. School meals are now provided; many of the vegetables are grown in a kitchen garden. Interestingly, in the garden I spotted a moringa tree (Remember this tree is native of the Sahel).

The unassuming-looking tree is like a super-food. Most commonly the leaves are crushed and the powder used to fortify soups, beans and all sorts of things.

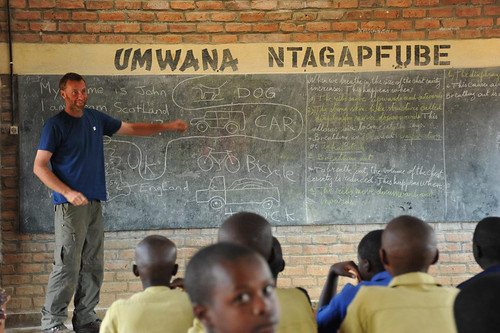

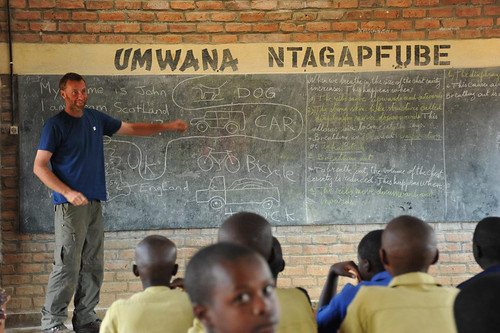

The school is very fortunate to have a computer laboratory and WiFi. Students are now able to be computer literate, receiving lessons regularly. Teachers of course have to keep up. Teacher training is provided to keep them up to date. As of last year, children in Rwanda learn in English rather than French.

The school is very fortunate to have a computer laboratory and WiFi. Students are now able to be computer literate, receiving lessons regularly. Teachers of course have to keep up. Teacher training is provided to keep them up to date. As of last year, children in Rwanda learn in English rather than French.

Many teachers have had to receive English lessons. John thought he would test out the students’ English knowledge and took an impromptu lesson for a year four class. You can see the result…”My name is John”, I live in Scotland.”Where is Scotland?” The students loved it.

Access to health was a major issue before 2006. So far sanitation has been improved with the new water pipeline. Health posts are being set up to take care of simply treatable maladies. Reproductive health was a major issue due to lack of facilities which is now being addressed. A whole new maternity wing has been added. We visited the newborn room. There have also been gains in the uptake of medical insurance with some simple education and promotion. Another big change is that everyone now has a mobile (cell) phone and full coverage thanks to a new cell tower constructed by Ericsson. They all know the free number to dial in the case of a medical emergency which has markedly improved access to medical attention.

After visiting the hospital, next on the packed agenda was a women’s handicraft program. The women’s weaving is to a high standard and an international market is being created. This project and now cooperative helps empower women, allowing them to contribute to the household income and gives them some extra motivation outside the daily grind of farming and bringing up the family.

Finally we were given a tour of the new cassava processing plant. The root from the cassava plant provides the staple food in their diet. The starchy tuber is peeled, washed, chopped in a machine not unlike a wood chipper, fermented, dried and ground into flour. Apparently the processing plant produces a high standard of cassava flour which in turn means higher returns for the farmers of the cooperative. The cooperative appeared to be working well and the workers seemed a very happy bunch.

Finally we were given a tour of the new cassava processing plant. The root from the cassava plant provides the staple food in their diet. The starchy tuber is peeled, washed, chopped in a machine not unlike a wood chipper, fermented, dried and ground into flour. Apparently the processing plant produces a high standard of cassava flour which in turn means higher returns for the farmers of the cooperative. The cooperative appeared to be working well and the workers seemed a very happy bunch.

That was the end of the Mayange tour. A lot was packed into one very interesting day and we sincerely thank Donald, Deo, Miriam and Jeanette for facilitating the visit and making it run so smoothly.

On the way back to Kigali we made a short diversion to see the Nyatama Memorial Site to the Rwandan genocide. John and I had already visited a memorial in Kigali which explains why it happened, events leading to the 100 days of frenzied killing and torture, the lack of response from the international community, the aftermath, child victims and about other genocides which have occurred over the last century. For me (and I think the others too) Nyatama was without doubt the most disturbing, horrific, emotive display I have ever experienced. Before I explain what we saw I think it is important to give a brief background of what I learned in Kigali.

Before German colonisation in the late 1800s and early 1900s the three ethnic groups in Rwanda, the Hutus (84%), Tutsis (15%) and Twa (1% – pygmies) lived in complete harmony, side by side. There is no evidence of any conflict. The Germans decided that the Tutsis, the minority group, were of higher intelligence and began to favour them for all the positions of importance and responsibility. Rwandans were classified a Tutsi if they owned more than 10 cows. The Germans also took anthropometric measurements, classifying a person a Tutsi if they had a longer thinner nose. After World War I, Belgium took over as the colonial power and continued with the same divisive regime. This of course bred descent amongst the Hutu majority which evolved over the next few decades into racial hatred. The first large scale conflict erupted in 1959, around the time of independence. The 1994 genocide was a deliberately planned; its architects (leaders, politicians, the media) manipulating, inciting violence, hatred and deepening divisions within the country. There were many warnings not heeded by the international community. Much could have been done to prevent or at least reduce what occurred during 100 days of madness when the Hutus attempted to eliminate the Tutsis and moderate Hutus who did not want to partake in the ethnic cleansing from the face of the planet.

Nyatama is a monument to humanity at its most evil. Many people fled to the Catholic churches such as at Nyatama to hide and seek sanctuary from the carnage, believing that they would be safe there. Many priests however betrayed their trusting constituents by turning them over to the Hutu murderers. At Nyatama over 5000 people – men women and children – were slaughtered. The aim was not just to kill, but to inflict as much pain and indignity as possible. As we walked in to the rear of the church, thousands of skulls were displayed on the higher shelves; some with spikes and other instruments of murder still embedded. The lower shelf was stacked with limb bones. Victims’ bloodstained clothes hung on the rafters and covered the side walls. There was a certain stench which I will never forget.

To the right of the altar, there was a collection of the victims’ most prized possessions; pendants, crosses, glasses, jewellery, personal belongings. At the altar women were raped, their wombs removed before they were shot. Our guide pointed out the spot where bullets had scarred the concrete. We were taken to the Sunday school classroom behind the church. Here children and toddlers were tortured and killed by being smashed against a wall. The blood stains are still there. Finally we were taken to another adjacent building. There people were wrapped with mattresses, petrol thrown over them and set alight.

To the right of the altar, there was a collection of the victims’ most prized possessions; pendants, crosses, glasses, jewellery, personal belongings. At the altar women were raped, their wombs removed before they were shot. Our guide pointed out the spot where bullets had scarred the concrete. We were taken to the Sunday school classroom behind the church. Here children and toddlers were tortured and killed by being smashed against a wall. The blood stains are still there. Finally we were taken to another adjacent building. There people were wrapped with mattresses, petrol thrown over them and set alight.

I did take a few photos, but decided to delete them all except the one shown (people’s possessions). I have also been deliberating as to whether I should write about what we saw at all. One of the main purposes of the Nyatama and Kigali memorials is to educate people about the genocide in the hope that the world will learn – with even more recent events of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and Serbia, I’m not sure whether the world has learnt, but these monuments send powerful messages and there is always hope. I read in a Ugandan newspaper last week that one of the priests who sought asylum in Finland has been convicted of his horrific crimes and jailed. Life in a Finnish jail might be too good for him, but at least another war criminal is brought to justice. In 1994 over a million people out of a population of seven million were slaughtered. Two thirds of the population were displaced. Many fled to neighbouring countries and 16 years later still not everyone has returned. John drove us back to Kigali. Barely a word was spoken.

We moved on the next day – I cycled out of Kigali and up a beautiful valley, over a high pass and into Uganda. All around me were smiling faces and many men cycled alongside me for a few kilometres at a time.

They have moved on too (at the very least, they get on with life). To see Rwanda now it is hard to believe what happened just a few years ago. Anyone over the age of 16 must have been present and must have some horrific memories, lost family members, been physically injured and mentally scarred. It’s hard to imagine how people can forgive after neighbours turned on each other. The international community has poured huge amounts of money into the tiny country to help Rwanda back on its feet. There must also be a pouring of immense guilt along with that.

This makes initiatives like Emmanuel’s One Love Project even more special – they are really making a difference. What has been achieved in just four years at the Mayange Millennium Village is testimony that Rwandan communities are resilient, proud and able to rebuild even after the most horrific experiences imaginable. They are all moving on to a better life.

Just a quick update to say that I have made it! After 22,040km I arrived at Cape Hafun, the most easterly point of the African continent on the 16th August, 4 days ahead of schedule. Our journey through Puntland was absolutely amazing and I have a great story to tell. I arrived at the remote lighthouse with a pistol in my bar bag and a split wheel rim. The wind was so strong that I was constantly being sand blasted and blown off the road. We have had incredible support from the Puntland government, from the president down.

Just a quick update to say that I have made it! After 22,040km I arrived at Cape Hafun, the most easterly point of the African continent on the 16th August, 4 days ahead of schedule. Our journey through Puntland was absolutely amazing and I have a great story to tell. I arrived at the remote lighthouse with a pistol in my bar bag and a split wheel rim. The wind was so strong that I was constantly being sand blasted and blown off the road. We have had incredible support from the Puntland government, from the president down.