Title: Garowe to Cape Hafun

Dates: 11th - 16th August GPS:

Distance: 585km Total Distance: 22.040km

Roads: 210km tarmac, 375km rough tracks, stones, sand

Weather: Extremely windy (tail, side and head winds), hot

Due to the tail wind and the fact that I was cycling with very few breaks, I arrived with my five vehicle entourage in Garowe by mid-afternoon on the 10th. Security was incredibly tight. We had guards at our side all the time. This may have felt very constricting for us but Issa, the president and all the government officials and their families must live this way all the time; virtually imprisoned in their own homes and offices. They can’t venture down the street or wander off for a walk. Issa’s wife, Anne-Marie and their two children, Bishaaro and Bilan have just moved to Garowe in the last month. It’s a huge commitment to move the family there. In the late afternoon after it had cooled down a little, everyone (except me) was in need of some exercise.

Due to the tail wind and the fact that I was cycling with very few breaks, I arrived with my five vehicle entourage in Garowe by mid-afternoon on the 10th. Security was incredibly tight. We had guards at our side all the time. This may have felt very constricting for us but Issa, the president and all the government officials and their families must live this way all the time; virtually imprisoned in their own homes and offices. They can’t venture down the street or wander off for a walk. Issa’s wife, Anne-Marie and their two children, Bishaaro and Bilan have just moved to Garowe in the last month. It’s a huge commitment to move the family there. In the late afternoon after it had cooled down a little, everyone (except me) was in need of some exercise.  Going for a walk however involves rounding up the security guards and bulletproof vehicles and driving to the hills out of town. Issa has to don his bulletproof vest and carry a gun. Anne-Marie and my sister Jane up the intensity of the exercise by jogging as we didn’t have long – just enough time to watch a beautiful sunset over Garowe. Garowe, the administrative capital of Puntland isn’t a very large town. Prior to the setting up of the state government in 1998, it was just a village.

Going for a walk however involves rounding up the security guards and bulletproof vehicles and driving to the hills out of town. Issa has to don his bulletproof vest and carry a gun. Anne-Marie and my sister Jane up the intensity of the exercise by jogging as we didn’t have long – just enough time to watch a beautiful sunset over Garowe. Garowe, the administrative capital of Puntland isn’t a very large town. Prior to the setting up of the state government in 1998, it was just a village.

The plans for the last stage were constantly evolving. There were two major issues to consider which affected our security, and ultimately whether or not I would have the opportunity to complete the expedition at Cape Hafun, the most easterly point of the African continent. The government was waging a war with Al Shabab just to the west of Bosaso, but the location of the conflict was not static. The military intervention had begun on 7th August, three days before we arrived in Garowe. I had been in constant communication with Issa over the last few weeks and knew about the pending conflict. The government forces were winning, having stormed the main training camp during our day in Garowe. A major concern was that splinter groups of Al Shabab soldiers had fled to hide in villages near our planned route to regroup. This was perceived to be the main danger for us.

There were a couple of route options. The original suggestion was to travel along the main road to within 60km of Bosaso before turning east to Hafun. This would have taken us dangerously close to the combat zone. The second option was a more direct route from Qardho to Hafun. It is a shorter distance but it was very hard to get reliable information about the rough road (tracks). The land is very remote so if we did get into trouble, it would have been very difficult to rescue us. The government has access to the best intelligence and were monitoring everything as it happened.

Even when we arrived in Garowe there was no foregone conclusion that I would be allowed to cycle to Cape Hafun. The other problem to bear in mind was the pirates. They are basically operating along the coast to the north and south of Hafun at this time of year, sheltering from the dominant north westerly winds. It would have been extremely disappointing if I had made it this far in a continuous line but couldn’t complete the ultimate goal. At the same time, I respected and trusted the advice and decisions made by the government. If the risk was too great I would never wish to endanger any of the team; my sister, Zdenek, Issa, Abdiwali (Deputy Minister for Livestock who volunteered to accompany us to the finish) or the soldiers.

The following day, after a visit to a private school (up to year 10), we had a meeting with Ali Yusuf Ali, Deputy Minister for the Interior, Local Government and Rural Development. We discussed the route plan and risks. He basically gave us the all-clear to travel to Qardho and then on the more direct, least travelled route to Hafun. This was pending the final word from the president whom we were going to meet over dinner in the evening. At this point I was able to prepare myself to at least cycle the first leg, 210km up the main road to Qardho.

The following day, after a visit to a private school (up to year 10), we had a meeting with Ali Yusuf Ali, Deputy Minister for the Interior, Local Government and Rural Development. We discussed the route plan and risks. He basically gave us the all-clear to travel to Qardho and then on the more direct, least travelled route to Hafun. This was pending the final word from the president whom we were going to meet over dinner in the evening. At this point I was able to prepare myself to at least cycle the first leg, 210km up the main road to Qardho.

We were honoured to be invited to dinner to meet the President of Puntland State, Dr. Abdirahaman M. Mohamed. During the first meeting in the reception room, he warned me of the potential dangers ahead from Al Shabab and the pirates. I explained that I fully respected his advice, but once the risks had been assessed, if it was deemed possible for the team to reach Cape Hafun safely, I was prepared for the challenge. Jane and I sat at the head of the table for dinner, either side of the president. During dinner (which included camel and goat meat, spaghetti, rice, salad and fruit), we were able to ask questions about the priorities of the Puntland government, what kind of international assistance they require, what kind of action is needed to improve the situation in Mogadishu and southern Somalia. Zdenek sat beside me capturing great images and recording our conversations.

We were honoured to be invited to dinner to meet the President of Puntland State, Dr. Abdirahaman M. Mohamed. During the first meeting in the reception room, he warned me of the potential dangers ahead from Al Shabab and the pirates. I explained that I fully respected his advice, but once the risks had been assessed, if it was deemed possible for the team to reach Cape Hafun safely, I was prepared for the challenge. Jane and I sat at the head of the table for dinner, either side of the president. During dinner (which included camel and goat meat, spaghetti, rice, salad and fruit), we were able to ask questions about the priorities of the Puntland government, what kind of international assistance they require, what kind of action is needed to improve the situation in Mogadishu and southern Somalia. Zdenek sat beside me capturing great images and recording our conversations.

Before the 1991-92 civil war, Mogadishu the capital of Somalia was the centre of everything; government, the education system, health, communications and development. To receive a higher education, for example, students from Puntland would need to travel to the capital.

Before the 1991-92 civil war, Mogadishu the capital of Somalia was the centre of everything; government, the education system, health, communications and development. To receive a higher education, for example, students from Puntland would need to travel to the capital.

During and after the war, anyone not from southern Somalia was expelled back to their homeland, such as Puntland, with no access to healthcare, education and little opportunity to generate a reasonable income. The Puntland government formed in 1998 as a response to the anarchic situation which evolved out of the failed central government in Mogadishu. The state government is made up of 66 politicians who represent each of the clans so that every clan has government representation and therefore a voice. Members of parliament are nominated by their clan elders and are expected to make a financial contribution. The members of government then elect the president and office bearers.

Most of the ministers grew up in Puntland but then left Somalia before or during the civil war to live and study in Western countries such as Australia, UK, Canada, US and New Zealand. They have all made the choice to return to form a government to make a difference to their homeland. Their commitment I find inspirational – the fact that they could have continued to have a comfortable Western lifestyle, but elect to return to their country and face constant danger and difficulties in order to improve the lives of their fellow Somalis.

The Puntland government does not wish to secede from the federal government, as they do in Somaliland, they have elected to work with Mogadishu and govern their people until such time as the Somali government can regain control. Their hope is for a federal government which would retain overall control of the Somali states including Puntland.

War and conflict pares development back to ground zero. With limited resources and funds, the government has a seemingly impossible mountain to climb, but the priorities the president outlined make perfect sense to achieve a more stable and sustainable future. Nothing can work without peace and justice, so eliminating Al Shabab and piracy is first priority.

War and conflict pares development back to ground zero. With limited resources and funds, the government has a seemingly impossible mountain to climb, but the priorities the president outlined make perfect sense to achieve a more stable and sustainable future. Nothing can work without peace and justice, so eliminating Al Shabab and piracy is first priority.

Education is a major focus. With inadequate facilities and number of teachers, the education minister is procuring scholarships in neighbouring countries such as Sudan and Kenya to educate their stronger students to a higher level. Encouraging trade and investment is essential to kick start the economy. Currently the main source of trade is from livestock export. Encouraging exploration for oil and minerals should inject funds into the state. Of course there is much more that I have not outlined here.

Dr. Abdirahaman, Issa Farah (Minister for Petroleum and Minerals), Abdiwali Hersi Nur (Deputy Minister for Livestock and Animal Husbandry), Farar Ali Jama (Finance Minister) – all of whom we met – are Australian Somalis. They looked after us like family, even contributing financially to help us through to the end. Issa basically mobilised the whole Puntland government who were unified in their support of us and the expedition. They ensured that we had the protection we needed, constantly accessing the best intelligence. The president gave us his blessing and provided us with his own special security forces for the first two days from Garowe to Qardho. We decided we should set off the next day. The longer we hung around Garowe and the longer I took to complete the journey, the greater the security risk. We continued to take care not to publicise our intentions or even write them in emails as they could be accessed by the wrong people.

We set off on the morning of the 12th for Qardho after President Abdirahaman farewelled us. This was the beginning of the end. The president’s guards led the way in their ‘technical’ through the streets of Garowe, sounding the siren every time the route was impeded by traffic. One bulletproof vehicle followed along with a normal 4×4 for a short while. Abdiwali, who committed to accompany us to the finish, travelled in the car with Jane and Zdenek. (Issa had to deliver intelligence materials to the war front and joined us in Qardho to travel to Hafun.)

We set off on the morning of the 12th for Qardho after President Abdirahaman farewelled us. This was the beginning of the end. The president’s guards led the way in their ‘technical’ through the streets of Garowe, sounding the siren every time the route was impeded by traffic. One bulletproof vehicle followed along with a normal 4×4 for a short while. Abdiwali, who committed to accompany us to the finish, travelled in the car with Jane and Zdenek. (Issa had to deliver intelligence materials to the war front and joined us in Qardho to travel to Hafun.)

A raging tail wind made my job much easier and I reached Dan Gorayo (112km) in very quick time. The landscape was fairly featureless until passing through a few hilly kilometres before our destination. The plains were vast with limited low vegetation supporting some grazing animals. Dust storms whipped up all over the place. I took just one tea break in a small village. While we had contact with a few of the women, the soldiers tended to keep most of the villagers away.

In the late afternoon we walked through a small IDP (internally displaced person’s) camp on the outskirts of Dan Gorayo village. Many who lived beside the coast lost their homes during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Most however had lost the bulk of their stock during fierce hail storms which occurred at around the same time. Abdiwali spoke to one woman who explained that she had lost more than 90% of her goats and sheep but she was gradually rebuilding her stock numbers.

In the late afternoon we walked through a small IDP (internally displaced person’s) camp on the outskirts of Dan Gorayo village. Many who lived beside the coast lost their homes during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Most however had lost the bulk of their stock during fierce hail storms which occurred at around the same time. Abdiwali spoke to one woman who explained that she had lost more than 90% of her goats and sheep but she was gradually rebuilding her stock numbers.

In the meantime, life was hard in the IDP camps. The shelters provided by the UNHCR were helpful but not sufficient for her family of six children, so she had manufactured a larger, sturdier home from whatever she could find to use for building material. Her flock had increased to 30 and she hoped to have 80 animals before too long. That would be enough for her to move on.

Between Dan Gorayo and Qardho, the road direction changed 90 degrees and I was battered by the strongest cross wind I have ever had to deal with (at this point). I was tossed around like a rag doll, often leaning at a big angle into the gusts. At our tea break we had a very interesting discussion with Abdiwali about the situation with Al Shabab and why they have become a formidable force.

Between Dan Gorayo and Qardho, the road direction changed 90 degrees and I was battered by the strongest cross wind I have ever had to deal with (at this point). I was tossed around like a rag doll, often leaning at a big angle into the gusts. At our tea break we had a very interesting discussion with Abdiwali about the situation with Al Shabab and why they have become a formidable force.

Somalian soldiers are trained at great cost to the government but some defect because Al Shabab can afford to pay their soldiers more. Al Shabab is funded by Al Qaeda and certain Arab businessmen and organisations. Abdiwali said that it is often difficult to know where some soldiers’ allegiances lie. The extremists prey on the vulnerable; the illiterate, poor and young, brainwashing them into believing that they will be better Muslims if they adopt their extreme practices. By sacrificing their lives they would be glorified in the name of Allah.

Their extreme practices have a negative effect on education, women, the economy, freedom… The purpose of the present conflict is to prevent these ideologies spreading like a cancer through communities and taking a stronghold.

In Qardho there was much discussion about the best route. I met the mayor who advised us about the distances, villages, terrain and road conditions. None of our maps showed all the settlements and the tracks they depicted were too general and often incorrect. I changed my tyres over to the off-road Schwalbe Marathon Extremes in readiness for the rough and sandy roads ahead.

Issa arrived back from the frontline, tired but ready to travel with us for the remainder of the journey. He said that the president had been very nervous about allowing us to go that morning and nearly called a halt. The fact that we were using two bullet-proof vehicles along with the ‘technical’ unit helped convince him to let us go through. We also said goodbye to the president’s guards as they had been called to the frontline. A new set of soldiers joined us having just returned from the conflict. Sadly we later learned that three of the president’s special forces who had protected us between Garowe and Qardho had been killed in an ambush.

I could not have imagined how the final three days unfolded. Sixteen kilometres out of Qardho we turned off the main tarmac road, heading east along a minor dirt track. I moved along well with a strong tailwind. Initially the terrain was flat easy-going clay pan, but then it deteriorated into stony outcrops and generally rough surfaces.

I could not have imagined how the final three days unfolded. Sixteen kilometres out of Qardho we turned off the main tarmac road, heading east along a minor dirt track. I moved along well with a strong tailwind. Initially the terrain was flat easy-going clay pan, but then it deteriorated into stony outcrops and generally rough surfaces.

For much of the day I had to inhale thick, fine dust. The plan for the first day was to slog it out and cover as much ground as possible. Small settlements were generally about 30-50km apart. After 67km we stopped for a small break in Cabaar village.

The reception was typically friendly – the women especially were intrigued. The fact that I looked very different to them in my cycle gear (I did wear long below-the-knee loose-fitting shorts) did not matter. We were treated like family and they cheered and danced to wish me well as I pushed on.

The reception was typically friendly – the women especially were intrigued. The fact that I looked very different to them in my cycle gear (I did wear long below-the-knee loose-fitting shorts) did not matter. We were treated like family and they cheered and danced to wish me well as I pushed on.

It was here that Issa explained the drill I had to follow if there was a gun shot. If I heard a shot I had to fall to the ground immediately and the two bullet-proof vehicles would drive either side of me forming a V-shape. One of the guards would then drag me in. I had been making such good progress, so this discussion was sobering. It was still not very likely, but it was essential know the plan.

The tracks cut a path through crumbling stony terrain and much Nullarbor-like country. The commander in the technical vehicle leading the way, followed by me and the two bullet-proof 4×4 vehicles. I felt extremely privileged to have the opportunity to cycle through this part of the world.

The tracks cut a path through crumbling stony terrain and much Nullarbor-like country. The commander in the technical vehicle leading the way, followed by me and the two bullet-proof 4×4 vehicles. I felt extremely privileged to have the opportunity to cycle through this part of the world.

I was making such good progress by early afternoon that I mentioned to Issa and Abdiwali that I could easily cope with doing 150km or so and they altered the plan accordingly to reach a certain village. Issa was regularly on the phone though trying to get directions and information from local sources. Also travelling with us was Yassin Mussa Bogor, security advisor to the president of Somalia. Yassin is also the grandson of the last king of this region.

I think only the commander and one of the 4×4 drivers had travelled through to Cape Hafun before although I am not sure whether any of them had taken this route. There were unmarked tracks peeling off regularly; some rejoined the main route although quite often it was impossible to tell which was the right option. I was still going strong as the sun set.

We were trying to reach a particular village called Marer because security-wise it was preferable to stay in a settlement than out in the open. The vehicles lit my way and I continued until about 8pm. Finally they conceded we were lost. I had done 190km by this stage and was well passed the tired stage and in to overdrive.

We were trying to reach a particular village called Marer because security-wise it was preferable to stay in a settlement than out in the open. The vehicles lit my way and I continued until about 8pm. Finally they conceded we were lost. I had done 190km by this stage and was well passed the tired stage and in to overdrive.

My Somali colleagues could not believe that I could keep going after nearly ten hours on bad roads; they thought I might be overcome with exhaustion and not be able to continue the next day. Although a little tired I was fine (albeit my knees were sore from having to absorb all the shocks), having done it all before.

The most worrying issue being that we were lost in the dark and in open space where we could be seen for miles. We waited while Abdiwali and the commander drove off to try to locate some nomads. They returned unsuccessfully and so we decided to set up camp near the best cover we could find.

Another important issue to consider was that it is Ramadan and the entire support crew (apart from Zdenek and Jane) were fasting during sunlight hours. The soldiers were supposed to organise their own supplies, but having joined us directly from the frontline, they did not have any food. We gave what we could, but it was not enough to sustain them through the night while they guarded the camp and the following day. I refuelled on spaghetti and a tin of tuna. Not fancy, but it did the trick.

Despite all the work Issa had been doing – travelling to the frontline, coordinating our journey and travelling with us – he insisted on doing a shift with the soldiers and had very little sleep. He is very much a team man and led by example. He showed great empathy with the troops who were so exhausted that some of them fell asleep on the ground as soon as we stopped.

At daybreak, Issa, Abdiwali and the commander were able to locate the nearest group of nomads and find out directions. The previous night they had thought we may have travelled about 20km in the wrong direction (rather frustrating for me), but we were pleased to learn that we had strayed only about 5km. Abdiwali bought two goats from the nomads to feed the soldiers. They had decided to break their fast to keep their energy up for the next couple of days. The goats were loaded on to the back of the technical and we returned to the junction where we went wrong.

At daybreak, Issa, Abdiwali and the commander were able to locate the nearest group of nomads and find out directions. The previous night they had thought we may have travelled about 20km in the wrong direction (rather frustrating for me), but we were pleased to learn that we had strayed only about 5km. Abdiwali bought two goats from the nomads to feed the soldiers. They had decided to break their fast to keep their energy up for the next couple of days. The goats were loaded on to the back of the technical and we returned to the junction where we went wrong.

I continued the line, cycling to the next village only six kilometres away. We then had to wait for four hours while the goats were slaughtered and cooked. Initially I was frustrated because having done so well the previous day we were in a position where we could reach Cape Hafun a day earlier. For security reasons, this was preferable. The longer we were out there, the more likely the wrong people could hear about our journey and plan an attack. I did not want to undo all the good work either. As it turned out, we were closer to our destination than we thought and the schedule was not altered.

We did not get going until 11.30am and so I had to pedal through the heat of the day virtually non-stop to reach our destination at a road builders’ camp called Foar, just to the south of the Hafun peninsula.

We did not get going until 11.30am and so I had to pedal through the heat of the day virtually non-stop to reach our destination at a road builders’ camp called Foar, just to the south of the Hafun peninsula.

The final two hours of the day’s ride were particularly memorable. We had reached the coast.

Dry wadis (ephemeral rivers) carved their way through rugged cliffs and a broad valley to the Indian Ocean. Cycling-wise this meant steep descents and ascents and some very stony ground. The river beds were deep sand, but not too extensive to cross. Again I arrived in the dark, this time completely drained of energy.

At Foar we were greeted by the villagers who prepared food (the usual goat’s meat and spaghetti) and honoured us with a traditional welcome. The Mayor of Hafun and a highly respected elder drove from Hafun to greet us and escort us through their region to the finish.

At Foar we were greeted by the villagers who prepared food (the usual goat’s meat and spaghetti) and honoured us with a traditional welcome. The Mayor of Hafun and a highly respected elder drove from Hafun to greet us and escort us through their region to the finish.

Hafun, an ancient port town, is virtually cut off from the mainland (by land). A sandy limestone-based 45km isthmus connects Ras Hafun to the mainland. An inadequate track which winds through the sand dunes is difficult for 4×4 vehicles to navigate.

The people of Foar are working to build a better road to connect Hafun using their own resources. Until now, no one from the government had been out this way, but now that Issa, Abdiwali and Yassin have travelled there, seen what they have achieved with their own motivation and efforts, they have promised to provide some support.

There air of excitement was palpable on the final morning; not just me, but from the whole team and villagers. In fact, Issa, Abdiwali and the soldiers seemed more excited than me. The women cooked a huge stack of Somali pancakes to sustain me throughout the morning. I knew that this day would be tough physically and reminded myself that many people fail at the last hurdle. I had to remain focused to reach the finish safely.

There air of excitement was palpable on the final morning; not just me, but from the whole team and villagers. In fact, Issa, Abdiwali and the soldiers seemed more excited than me. The women cooked a huge stack of Somali pancakes to sustain me throughout the morning. I knew that this day would be tough physically and reminded myself that many people fail at the last hurdle. I had to remain focused to reach the finish safely.

Issa, Abdiwali, myself and Yassin all made thank you speeches; the politicians reaffirming that they would assist them to make the road. The village leader in turn mentioned that they may name the road after me – a great honour I said.

The road quality for the first few kilometres was quite good, even though I had to battle the strong crosswind which lifted sand straight off the huge ergs (sand dunes). The road quickly degraded into sand drifts and then deep sand.

The road quality for the first few kilometres was quite good, even though I had to battle the strong crosswind which lifted sand straight off the huge ergs (sand dunes). The road quickly degraded into sand drifts and then deep sand.

Cycling this section was no different to cycling on normal beach sand. The road builders had placed large stones like loose pavement where the sand collects across the path in the hope of stabilising the track. Unfortunately the sand between the stones had blown away leaving gaping crevasses, making it almost impossible to cycle. Then came the deep sand.

I managed to find slightly firmer ground away from the track (which had been churned up by vehicles). All three vehicles became bogged and so the soldiers ran with me where they could. Eventually the commander caught me and asked me to stop to wait for the entourage. All I wanted to do was get to Cape Hafun as quickly as possible. Issa eventually caught up too.

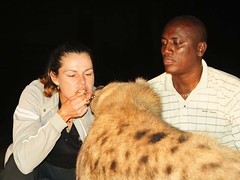

They had been worried because all they could see was me disappearing off the track and through the bush. I am used to cycling in sand and searching for the best path and was confident that I knew what I was doing. They didn’t know that. A nomad they’d just met had just lost a number of his livestock due to hyenas. Issa decided to loan me his 9mm pistol so that I could protect myself from hyenas and to attract attention if I became lost.

I was a little hesitant as I had never used a pistol before and thought I’d be more likely to shoot myself in the foot or something! Issa and the commander gave some instruction and I practiced squeezing the trigger before it was loaded and the safety catch set. The pistol sat in my barbag for the rest of the journey.

I was a little hesitant as I had never used a pistol before and thought I’d be more likely to shoot myself in the foot or something! Issa and the commander gave some instruction and I practiced squeezing the trigger before it was loaded and the safety catch set. The pistol sat in my barbag for the rest of the journey.

I decided to further reduce the tyre pressure while I was in the sand. At that point I noticed a split in my rear wheel rim. The crack was about four inches long and leading towards the hole for the valve. This was a serious injury for my bike. I had been carrying my spare bike all the way across Africa, but decided to leave it in Berbera and just take essential tools and spares.

The wheels had been hand built and I was impressed that I had not broken a spoke for the whole journey. I had checked the rims which remained perfectly true and as there was little room in the vehicles, decided to leave the spares behind. I was worried about the rim and removed the rear bags. If I was going to hit rough road, I approached the obstacles gently and leaned as far forward as possible to take the weight off the back wheel. With just 50km to go, I was afraid it would not last.

It wasn’t long before we had traversed the neck of the isthmus and turned on to the tidal flat, led by the mayor and his vehicle. I made reasonably good pace along the flat. Although it was heavy going at times there was effective shelter from the wind. The vehicles had to hug the more solid beach, otherwise they would become bogged. There was a race against the rising tide. At one stage, not long before we headed away from the beach towards Hafun, the sea was only a couple of metres from the beach.

Turning away from the beach I had to struggle along a sandy track with gale force cross winds. Sand blasting was severe and I joked that it was blowing in one ear and out the other.

Turning away from the beach I had to struggle along a sandy track with gale force cross winds. Sand blasting was severe and I joked that it was blowing in one ear and out the other.  I kept getting grit in my teeth. We paused in Hafun for a short break. Hafun has an ancient history as an important port dating back to Egyptian times.

I kept getting grit in my teeth. We paused in Hafun for a short break. Hafun has an ancient history as an important port dating back to Egyptian times.

The town was destroyed by the Indian Ocean Tsunami in 2004 when the wave washed right across the isthmus, wiped out the buildings and messed up the open sewage system. The town had to be rebuilt beside the old settlement. The Italian-built salt works and jetty lay decaying beside the old town along with some garrison buildings before the entrance. The salt works was only used for about 15 years and had been disused since the Second World War.

Jane and Yassin attached the Australian flag to a makeshift pole. I had carried the flag right across the continent to fly at the finish. The Mayor of Hafun attached a Somali flag to his vehicle’s antenna. Issa arranged for me to be interviewed on BBC World Service – Somali section.

We were ready for the final stage; 22km up the mountain and across the tabletop. The mayor wanted to get full value out of the moment and led me up and down the main street to parade the event to his people. I obliged, smiling and waving to enthusiastic townsfolk.

Climbing away from the town, the wind became worse. I was constantly blown off the road and it was even more difficult to control the bike as I had to deal with large loose gravel stones and steep inclines.

Climbing away from the town, the wind became worse. I was constantly blown off the road and it was even more difficult to control the bike as I had to deal with large loose gravel stones and steep inclines.

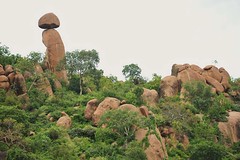

The track – I called it a billygoat track – wound up through a dry wadi and the side of the 210m Ras Hafun. The limestone plateau was completely exposed. Nothing grew more than a foot off the ground in this desolate place. Spiky acacia trees and shrubs grew flat over the surface due to the constant wind.

Our path across the island gradually deteriorated. The protruding pavement of stones had weathered into sharp edges. I had to be careful with my broken wheel while avoiding punctures from the thorns.

Finally Issa and the mayor pointed out a speck in the distance – the lighthouse. Now I was becoming excited. The track basically disappeared and about 2.5km from the lighthouse we had to walk. Of course I had to drag my bike over stones and around thorny acacias.

Finally Issa and the mayor pointed out a speck in the distance – the lighthouse. Now I was becoming excited. The track basically disappeared and about 2.5km from the lighthouse we had to walk. Of course I had to drag my bike over stones and around thorny acacias.

Some of the party raced ahead to cheer me as I arrived. There were very happy scenes. No one had been out there for a long while (the lighthouse and buildings are in disrepair) and the elder and mayor confirmed that they had never seen a cyclist reach this point.

They should know because any cyclist would have to pass through Hafun and would need directions and a guide to find the most easterly point of Africa. I was very proud – as was my sister – to complete the journey from Point Almadies, near Dakar in Senegal to Cape Hafun in a continuous line.

They should know because any cyclist would have to pass through Hafun and would need directions and a guide to find the most easterly point of Africa. I was very proud – as was my sister – to complete the journey from Point Almadies, near Dakar in Senegal to Cape Hafun in a continuous line.

Not a kilometre has been missed (except for river crossings). I could see that Zdenek was quietly chuffed with himself too. He has done a great job.

It was a huge commitment to drop everything and join the team in northern Cameroon and then to see the expedition through to the finish. Issa, Abdiwali, the Mayor of Hafun, the soldiers were all celebrating; the soldiers fired into the air to signal the finish.

While I am the only cyclist, this has been a team effort which has been made possible by a large number of sponsors and supporters. A special mention must be made to the other team members on this expedition who have been involved in expedition support and filming; John, Zdenek, Daniel, Simon, Paddy and Stuart.

Of course I would have never had the opportunity to reach the most easterly point of Africa without the support of the whole Puntland State government mobilised by Issa Farah. Omer Jama from Somaliland had a significant part to play as well.

Of course I would have never had the opportunity to reach the most easterly point of Africa without the support of the whole Puntland State government mobilised by Issa Farah. Omer Jama from Somaliland had a significant part to play as well.

I would have liked to stay around longer to absorb the moment and what has been achieved but the sun would soon set and we had to get back to Hafun.

The return journey to Bosaso was interesting and eventful too, but I will have to write about that in the next instalment.

The return journey to Bosaso was interesting and eventful too, but I will have to write about that in the next instalment.

{ 24 comments }