Title: Tsumeb to Livingstone, Victoria Falls

Dates: 20th to 27th April GPS:

Distance: 1078km Total Distance: 13,760km

Roads: Good tarmac, pretty flat

Weather: High 20’s – low 30’s Celsius, moderate to slight headwinds on average

Up until Etosha National Park we had seen very few wild animals during our journey, but our two day visit to the 23,000 square kilometre sanctuary has changed all that. Not many wild animals are seen outside the parks because basically there are too many people to accommodate sustainable numbers. Loss of habitat and bushmeat are the two main reasons. Any animal is fair game for local villagers and bushmeat is often for sale on the roadsides and on the menu in restaurants. Namibia is the only African nation with conservation firmly in their constitution. Since independence in 1989 – perhaps an opportunity to create a more practical environmental agenda for the times – I learned that the country has made significant progress with increasing numbers of black rhinoceros and cheetahs in particular. The Etosha National Park, 80km north of Tsumeb, is Namibia’s showpiece. The word ‘etosha’ means ‘Great White Place’ referring to the enormous saltpan (4700km square) around which the animals live and the limestone-based grounds. The park was proclaimed over 100 years ago, which must make it one of the first designated conservation places in Africa (I’d imagine).

We left the bikes and some unneeded equipment at our campsite in Tsumeb and drove back to Etosha. The park is easy to drive through, with good quality roads and plenty of side tracks, which usually lead to waterholes. Of course no one is allowed to get out of their vehicles (except in protected areas), and no cycling is permitted as there are plenty of man-eaters in the park. Once through the eastern gates at Namutoni, we were all amazed at the numbers of grazing animals that we didn’t know where to point the cameras – springboks, zebras, giraffes, impala, hartebeests were immediately on show. Before the expedition I had bought a fantastic 80-400mm lens so I could get some great animal shots, but unfortunately it is back in Australia for repair, so the photos you see are just from a 28-120mm lens. This means, of course, that the animals had to be close for me before taking a photo was worthwhile.

Perhaps the highlight of the first afternoon was the rhino sighting. Dan spotted it first in the veldt. Simon stopped the LandRover and the huge bulk wandered behind the vehicle, then started to casually walk towards us before heading across the road. Despite their size, rhinos are quite nervy, timid creatures with very bad eyesight. We stayed at Halali campgrounds and lodge in the middle of the park on our first night. All three main resorts have floodlit waterholes where patrons can sit and watch for animals to do their thing. Halali reportedly has the best one. It’s a bit like going to the theatre while the play is in progress. The audience creep in quietly in the dark, trying not to trip over the rocks or make a sound, not even whisper. The animals are the actors, stars of the show. The main difference is that they haven’t done any rehearsals and rarely turn up on cue. As we arrived, a kudu was munching the grass, nervously hanging back to check for any predators. Then a small rhino appeared on the far side. The two kept us entertained for quite some time. I loved the moment when the rhino, whose belly was pretty close to the ground, found a log which was just the right height for it to scratch its undercarriage. The rhino had a great time rocking back and forth over the log in pure bliss.

Perhaps the highlight of the first afternoon was the rhino sighting. Dan spotted it first in the veldt. Simon stopped the LandRover and the huge bulk wandered behind the vehicle, then started to casually walk towards us before heading across the road. Despite their size, rhinos are quite nervy, timid creatures with very bad eyesight. We stayed at Halali campgrounds and lodge in the middle of the park on our first night. All three main resorts have floodlit waterholes where patrons can sit and watch for animals to do their thing. Halali reportedly has the best one. It’s a bit like going to the theatre while the play is in progress. The audience creep in quietly in the dark, trying not to trip over the rocks or make a sound, not even whisper. The animals are the actors, stars of the show. The main difference is that they haven’t done any rehearsals and rarely turn up on cue. As we arrived, a kudu was munching the grass, nervously hanging back to check for any predators. Then a small rhino appeared on the far side. The two kept us entertained for quite some time. I loved the moment when the rhino, whose belly was pretty close to the ground, found a log which was just the right height for it to scratch its undercarriage. The rhino had a great time rocking back and forth over the log in pure bliss.

There’s no doubt that the highlight of the following day was spotting lions at Sueda Waterhole. I actually thought the male was a small elephant at first – it was huge! There was a lioness with him. They had probably either just made a kill (breakfast) or were ‘courting’. Almost as soon as we sighted them, they lay  down for the day using the shade of the long tufts of grass. Later that afternoon we returned, on the way back to Namutoni Resort in the hope that they might still be there. And they were, but on closer inspection through the binoculars, we counted a whole pride of lions. The male had a harem of seven girls. The first two had not moved, except to follow the shade of the bush they were lying under. They were totally relaxed – some lying on their backs, some with paws draped over another. Just as we were about to head off, Dan spotted two more lionesses, one asleep in a much closer location; another arriving from another direction, moving with caution.

down for the day using the shade of the long tufts of grass. Later that afternoon we returned, on the way back to Namutoni Resort in the hope that they might still be there. And they were, but on closer inspection through the binoculars, we counted a whole pride of lions. The male had a harem of seven girls. The first two had not moved, except to follow the shade of the bush they were lying under. They were totally relaxed – some lying on their backs, some with paws draped over another. Just as we were about to head off, Dan spotted two more lionesses, one asleep in a much closer location; another arriving from another direction, moving with caution.

The highlight of the final morning, as we drove around Fischer’s Pan, was seeing a family of elephants. The huge male made sure we knew who was boss as he walked between us and his group to protect them. Here’s a list of the animals we saw – and identified – in Etosha: Lions, blackbacked jackal, cape fox, spotted hyena, suricate, elephants, warthog, black rhinoceros, giraffe, Burchell’s zebra, steenboks, springboks, gemsboks, blue wildebeests, kudu, hartebeests, impala, ground squirrel, honey badger, ostriches, martial eagle, kori bustards, southern yellow hornbills, lilac-breasted rollers, Swainson’s spurfowl, starlings, owls and a few more. The main animals we missed that were there were cheetahs and leopards – but there has to be some big animals left to see another time!

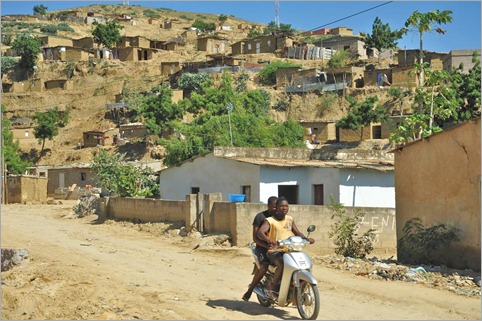

I was determined to cover some decent distance, even catch up a day on the way to Nunda River Lodge, near Divundu, West Caprivi. From Tsumeb I headed south east to Grootfontein, 60km away. Grootfontein has pride of place on this expedition as being the most southerly town we visit. From here, I start heading north east – finally in the right direction towards Somalia! There was something very satisfying about that and with the wind in my favour for the rest of the day I made good ground, covering 192km. The landscape was very open veldt – large privately owned cattle-grazing farms. I spotted a few Southern Cross windmills which made me feel at home. We camped at a roadside truck stop at the border between the Grootfontein and Kavango Regions. The next day, although the physical landscape looked similar, the cultural landscape was quite different. The Kavango Region is much more heavily populated with the original inhabitants. I passed through village after village with all sorts of handicrafts for sale by the side of the road and an overwhelming number of welcoming “hellos”. There is certainly no apartheid here and I learned that Namibian blacks don’t have the same resentment for the white minority as there is in much of South Africa, but there appears to be certain parts of the country which are more heavily populated by one or the other. This, of course is just an observation in northern Namibia, and I don’t know enough to understand how the regions are organised. After Rundu, I cycled due east parallel with the Kavango River, rising to my little personal challenge and reaching Divundu in three days after 532km.

Nunda River Lodge was flooded when we arrived. The Kavango River was the highest it has been, I think they said, for a century. We are now in the tail end of the Rainy Season and heavy falls up in the Angolan mountain catchment area have caused havoc downstream. The Kavango River passes through the west end of the Caprivi Strip and into Botswana, emptying into the sands of the Kalahari Desert forming the renowned wetlands known as the Okavango Delta. To complete the geography lesson for the day, the Caprivi Strip is a long narrow tongue of northern Namibia, dividing Angola and Zambia in the north from Botswana in the south and Zimbabwe to the east. The German colonials wanted access to the Zambezi River so that they could connect with their empire in Tanzania and marked the strip as theirs in the big divide up of Africa.

Nunda River Lodge was flooded when we arrived. The Kavango River was the highest it has been, I think they said, for a century. We are now in the tail end of the Rainy Season and heavy falls up in the Angolan mountain catchment area have caused havoc downstream. The Kavango River passes through the west end of the Caprivi Strip and into Botswana, emptying into the sands of the Kalahari Desert forming the renowned wetlands known as the Okavango Delta. To complete the geography lesson for the day, the Caprivi Strip is a long narrow tongue of northern Namibia, dividing Angola and Zambia in the north from Botswana in the south and Zimbabwe to the east. The German colonials wanted access to the Zambezi River so that they could connect with their empire in Tanzania and marked the strip as theirs in the big divide up of Africa.

My former cycling partner, Greg Yeoman had connected me to Nunda Lodge and I planned to have a day off there to meet the Kwe / San people, original inhabitants of the region. Trevor and Eugene, the lodge owners, kindly sponsored our stay. Moira Alberts, (Greg’s contact) had just started management work there a week prior to our arrival. It was great to finally meet them after trading many emails over the last couple of months. Nunda is a top end place to stay and I am particularly impressed with the way they are managing their ecotourism. (lodge@nundaonline.com)

In the afternoon, Dan, Zdenek, Trevor, Moira and I met with Friedrich Alpers and three Kwe people to learn about their issues, particularly as a marginalised group. Friedrich works for the IRDNC (Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation), which is a Namibian support NGO working the 5000 people (mostly Kwe) who live inside the adjacent Bwabwata National Park (formerly the Caprivi Game Park). The three Kwe whom with we met, Tienie, Vasco and Jack are representatives of the Kyaramacan Association who act for those living in the park.

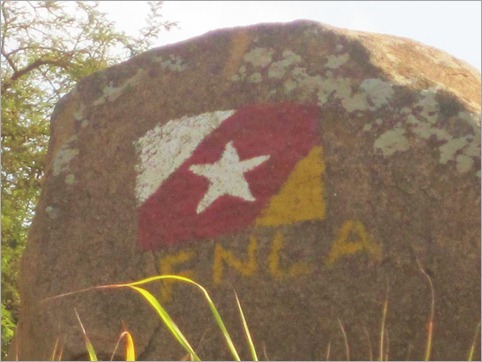

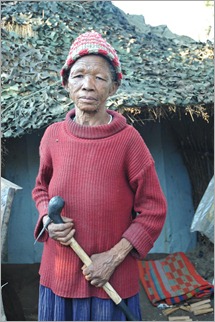

I first read about the plight of the San people when researching the expedition as UNESCO has identified their need for development assistance as a marginalised group and have a program in the larger community at Tsumkwe. There are about 12 different groups of San (formerly bushmen) living in southern Africa, the Kwe being one of these groups. It is well-documented that these people are genetically closest to the origin of mankind. They have the most diverse range of genes of any group of people on Earth. The Kwe of west Caprivi have had a hard time in recent years. During the war of independence between the South Africa (who were administrating Namibia up until 1989) and the Namibia, the SA military were stationed on the Caprivi Strip. They were also there during the Angolan war. The Kwe were forced to take sides, and as the SA military were there, they chose to work for the South Africans, particularly as trackers because of their amazing bush skills. After independence, the Namibian government has remembered this and they have been marginalised ever since. Tienie, Jack and Vasco gave their side of the story. Tienie said they had been given basic handouts, which has created a feeling of expectation and dependency. Unemployment is very high and alcoholism is a huge problem. He said in schools, even the children are discriminated against and sometimes even sent away. They have two headmen in their community, but stronger leadership is required to pull the communities together (there are 10 communities in the Bwabwata NP) and communicate with the government.

I first read about the plight of the San people when researching the expedition as UNESCO has identified their need for development assistance as a marginalised group and have a program in the larger community at Tsumkwe. There are about 12 different groups of San (formerly bushmen) living in southern Africa, the Kwe being one of these groups. It is well-documented that these people are genetically closest to the origin of mankind. They have the most diverse range of genes of any group of people on Earth. The Kwe of west Caprivi have had a hard time in recent years. During the war of independence between the South Africa (who were administrating Namibia up until 1989) and the Namibia, the SA military were stationed on the Caprivi Strip. They were also there during the Angolan war. The Kwe were forced to take sides, and as the SA military were there, they chose to work for the South Africans, particularly as trackers because of their amazing bush skills. After independence, the Namibian government has remembered this and they have been marginalised ever since. Tienie, Jack and Vasco gave their side of the story. Tienie said they had been given basic handouts, which has created a feeling of expectation and dependency. Unemployment is very high and alcoholism is a huge problem. He said in schools, even the children are discriminated against and sometimes even sent away. They have two headmen in their community, but stronger leadership is required to pull the communities together (there are 10 communities in the Bwabwata NP) and communicate with the government.

There is hope though. Friedrich and the IRDNC are working with the Kyaramacan Association on projects which aim to increase benefits from natural resources from within the park, tourism and how to manage the park and resources sustainably. The park was decimated during the military occupation and from poaching. Some of the region was also devastated by landmines. The Kwe however are now managing to reverse the damage. In the 200km-long park two areas have been sectioned off as core conservation areas, where only animals exist and are protected. In the rest of the park, man and animals co-exist. Hunting is essential to the Kwe way of life but the Namibian government has embargoed the practice. The Kwe will manage hunting in the future by only hunting in officially sanctioned groups rather than individuals hunting at will, so that numbers of animals hunted can be controlled and endangered species are not taken. At the moment, Friedrich is assisting them with documenting all the resources in the region using local knowledge (from thousands of interviews) and scientific observation. A fantastic resource map of the region has been created. With all the information, they can negotiate with the government and argue their case for controlled hunting and land management in the park. Friedrich is guiding them so that they have a stronger voice.

There are many parallels with the situation I found visiting the Baka in Cameroon – with Plan’s Rights and Dignity Project. The Kwe are a little further ahead in development. Both groups have been fast losing their incredible bush skills, but the Kwe now have a priority program where the elders are transferring traditional skills to the next generation. One of the most valuable veldt resources in the park is the tuber plant called Devil’s Claw. It is used in the treatment of arthritis and prostate cancer. Devil’s Claw is very much in demand in Europe. Friedrich has helped them gain an ‘organic’ tag (will qualify for this next year), which further increases the value of the product. If the Baka could market their diabetes treatment in the same way, this would surely help them significantly.

Tienie invited us to visit his village and so I just cycled a half day to Omega 1, the largest of the Kwe villages, population approximately 4600 people. Omega 1 was an army base for the South African military. During occupation, many of the Kwe were employed by the army and when they moved out, the villagers inherited the houses and infrastructure. The village is therefore unusual because they don’t live in traditional mud and thatched houses. Tienie was a great host and guide. Once the headman gave us the all clear we toured the town. It was a Saturday afternoon and most activity was either on the soccer field or drinking a strong homemade brew. We saw (and later bought) some traditionally woven baskets, made from reeds and coloured with natural dyes. They are only made in this way by a few ladies in Omega 1. Sport, Tienie explained was very important to the younger folk of the community because it is good for self-esteem, keeps people fit and gives them something to do. They play football, netball and volleyball. There is some farming land which is the result of various projects over the years. Some of the workers however have to walk up to 18km to work on their land. They do make their own tools – the blacksmith was out when we visited, but his wife demonstrated how they were made.

We set up camp, but overnight it rained and when I awoke my tent was virtually floating in a huge puddle. We used the office for shelter, but the rain continued and so we missed the opportunity to see a special honey/bee project. We said our thankyous and goodbyes, but the rain did not stop for most of the day. The aim was to at least get to Kongola just outside the park – a standard day in normal circumstances, but because we left at about 10am and I had a tricky headwind, I struggled to get there. The boys set off mid-afternoon to sort out our campsite with the plan that Simon would return to lead me in. He was held up pulling someone out who was bogged and the last 15km through the second core section of the Bwabwata NP was done after the sun set. It was eerie and I noted a warthog staring at me from about 20metres. Then I started to think what other animals might be watching. I knew there were lions… I started to get nervous and upped the pace. I was so relieved when Simon arrived. He then told me that the guard on the gate had said there were many lions in this end of the park “and you should not leave your wife on her own…” It was not a pleasant experience and I must admit, I was scared.

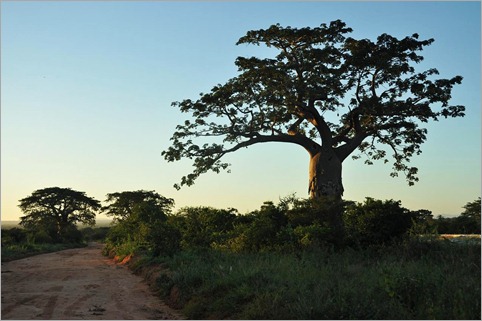

By the end of the following day we were over the border and in to Zambia, country number 13 of the expedition. Just after the border we crossed the Zambezi River which was also really moving fast, the waters very high. The boys said they were feeling a little burnt out and so I promised them two full days off in Livingstone/Victoria Falls. From Sesheke, however this meant a monster day. Basically to get there involved cycling for at least ten hours at 20km an hour. For most of the day I was held back by a nagging little headwind which made keeping the pace difficult. This also meant very short breaks and just concentrating on 50km sections at a time. I did manage to enjoy the mopane woodland and people’s friendly waves – I had to keep the mind busy and fill my head with positives – the only way to approach such a marathon. I won in the end though, Simon providing the light for the last 20km into Livingstone – 204km done in 10 hours, 20mins at 19.77km an hour!

Victoria Falls was the reward – one of the most amazing natural wonders I have ever seen. The river was so high that the mist cloud impeded much of the view. The power of the water was immense. The photos say it all I think. We’re heading north to Lusaka next where we have a number of project visits to do.

{ 4 comments }