Title: Ngaoundere to Yaounde

Dates: 4th to 18th Feb GPS:

Distance: 1332km Total Distance: 8202km

Roads: 645km difficult gravel; 687km tarmac; steep mountains, flat coastal tropics

Weather: Cool at altitude, extreme humidity at approx 32degrees in lowlands

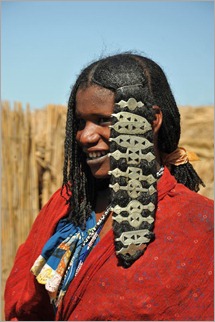

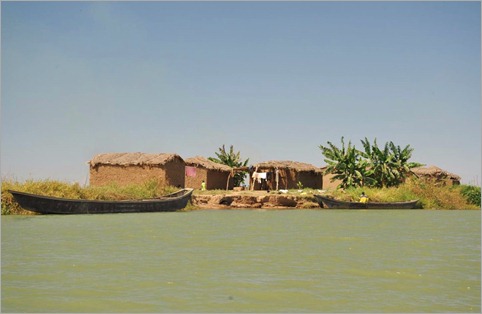

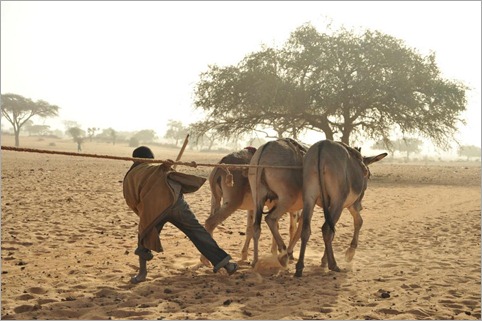

We stayed at the aptly named ‘Nice Hotel’ in Ngaoundere; clean, excellent staff, good food, good value – rare to find in our experiences of African town hotels so far. In fact Ngaoundere, the major junction town where the main roads meet and the railway from the south terminates, is a refreshingly well-organised town from our experience. Even the internet was reasonable (all relative though). While the main roads north of the town are all good sealed roads, from Ngaoundere we knew the standard was going to be poor whichever way we chose to go. The road to the south east through Bertoua is a little shorter but it is also the main truck route and by all reports, in appalling condition. We chose the westerly route through Tibati and Banyo – also frequented by heavy lorries transporting goods from Nigeria, the port and capital Douala and the west country. As with much of this expedition I have not chosen the most direct route as this is a voyage of discovery and there is much to see in the English-speaking North West province and south coastal region. By reaching and climbing Mount Cameroon in the south west corner and catching a glimpse of the ocean, we completed a comprehensive cross section of the country, experiencing something of each of the five main climatic zones of this “Africa in miniature”; Sahel/desert, savannah, mountains, tropical rainforest and coastal.

Firstly I had difficulties finding the main road. As usual there were no road signs to direct me to the main route to Tibati. Eventually after missing the turn-off and asking a number of truck drivers and moto-taxis I found the gravel road. The first section was well-made and it was easy to avoid most of the many corrugations. There were many short sharp ascents and descents but basically the road remained at roughly 1100m altitude as it wound its way through verdant green forests and villages. There were many rain barriers which mean that the road is closed after rain to protect the surface quality. The type and diversity of vegetation is evidence that we have entered a new climatic region. The desert and Sahel is now well behind us. The next time we will reach a similar zone will be in Namibia in the Southern Hemisphere, and then we will return to these latitudes in Ethiopia and Somalia for the final stages of the expedition. About 100km out from Ngaoundere, the climbs started to become a little steeper and care had to be taken to keep control on the descents. We camped in a beautiful meadow first night out from Ngaoundere at 1100m, where for the first time we had to deal with heavy grassy dew overnight. Our tents were soaking wet in the morning.

Given that most of the next week I would be travelling on unsealed roads, I decided to change my tyres – the Schwalbe ‘Expedition’ tyres are fatter and have much more tread to cope with rough and soft conditions, however they are less efficient on sealed roads. I worked very hard in the morning as the terrain became more challenging. At the 48km mark I was at the start of a steep descent. I thought I was going carefully but the true rocky surface was masked by a thick blanket of bulldust, sometimes about 30-40cm deep. (Those who have travelled through outback Australia will be familiar with bulldust; dust as fine as talcum powder caused by constant heavy traffic on dirt roads) On these mountain tracks, bulldust is the curse of drivers, motorcyclists (and this cyclist) on all steep ascents and descents. My front wheel hit a large rock and unable to brake effectively, I came flying off, diving head first, badly grazing my elbow in particular. I lay there for a few moments assessing the damage – no broken bones; the bike was okay – just a few dirty wounds and a little shock. I pulled to the side to wait for the team. Five minutes later a motorcyclist came careering down the slope, crashing in the exact same spot as I. I helped him up. He was also in shock. The Land Rover arrived about 15 minutes later and John did a great job cleaning the wounds and patching me up. The main issue was to prevent infection. We decided to have an early lunch to allow me to fully recover from the shock. Needless to say I took it very carefully for that afternoon and the next few days on these terrible roads. Road conditions deteriorated on the 115km track from Tibati to Banyo; even steeper inclines, worse bulldust and heavy truck traffic. Vehicles obviously still travelled when the road was wet so the surface was often just a continuous procession of giant potholes (3 metres wide, a metre or so deep), dust, rocks and corrugations. To see how some of these massive trucks negotiated these conditions was astounding. Sometimes they would have wheels completely airborne. Drivers were generally very courteous. Some would actually stop and wait for me to slip by – and I would wait for others to pass at times. The dust was so thick it was impossible to see or breathe without pulling my scarf over my mouth and nose. The Land Rover travelled at about the same speed as me. I came off a few more times; once landing directly on the injured elbow, but there was no more major damage. It was a relief to reach Banyo.

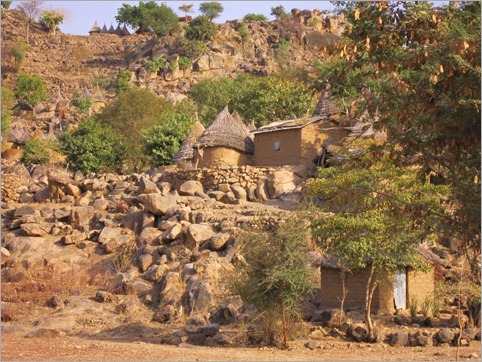

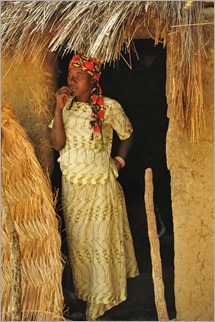

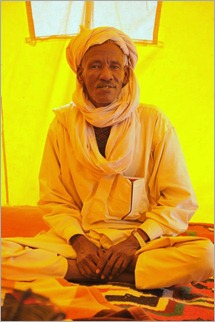

From Banyo the road was still gravel but of better quality. The many steep sections were sealed to prevent bulldust. At the village of Mayo Darle we stopped at the primary school to watch the kids march off to their morning exercise classes. The session was very regimented. Each class marched in formation and sang as they passed. Even the little ones practiced the drills outside their classroom. I spoke to the head teacher, Evita, who was in charge of the 760 students. There were too many children to teach in the school facilities so classes were divided into morning and afternoon sessions. There are major difficulties getting teachers to work away from the cities, so the overworked staff have to manage classes of about 50 pupils. Teachers get paid about $20 per day, which doesn’t go far in these parts. 30km further on we turned off the busy main road, across the plains towards the high mountains of the North West Province. I cycled through beautiful rainforest with so much diversity. For the first time we spotted coffee being grown and in front of some houses it was laid out to dry on mats. At Sabongari we turned off towards the looming high pass. There were no obvious camping spots so at Ngu, Dan asked the village chief for permission to camp on the school field. Needless to say we had a big audience as we set up.

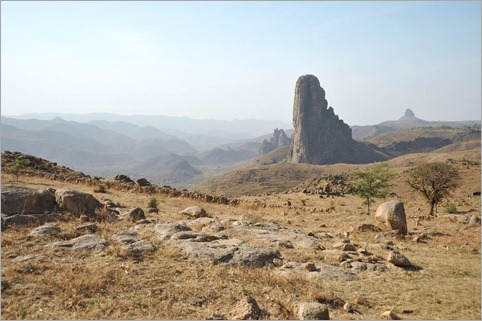

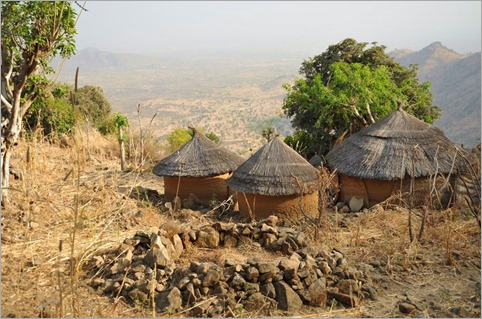

Ngu to Ndu was really only a half day but it involved the first true mountain pass of the expedition. Over the next 18km I cycled from 700 metres to 2060 metres. The first 8km in particular was so steep it was a real battle to turn the pedals. The key is not to stop to avoid a mental defeat. I’d estimate the gradients were at least at 20%. I had to pull so hard on the handlebars that at times I lifted the front wheel off the ground. Once at a decent altitude, the road wound its way through a few small villages. The volcanic soils appeared very fertile and the steep terraced slopes produced all sorts of fruit and vegetables – available for sale on the roadside. At 2000m we reached a very different land; cooler climate, tea and eucalypt plantations.

The climate and vegetation were not the only elements to have changed – language too. In the lower lands everyone spoke French, but as we reached Ngu and started to climb, more and more people greeted me in English, so that by the time I reached the top I switched to saying “Hello” and “Good Morning” rather than “Bonjour” and “Cava”. The North West Province is English-speaking which made conversing much easier. Ndu was definitely a British colonial town with tea houses and many other colonial influences. The region, like the southern half of the country, is strongly Christian and different churches appear to compete for patrons; in particular Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics and Evangelists. In Ndu we stayed in the Baptist Mission on recommendation from Martin (our guide in northern Cameroon). In many places throughout Cameroon we’ve stayed in different missions (Catholic, Baptist and Presbyterian) and they all provide cheap, clean, secure accommodation. Ndu was no exception. We learned a lot about the region from David who through his good will is giving ‘a leg up’ to many local organisations, providing furniture for the local schools and helping small businesses organise themselves into cooperatives to have a voice and more selling power.

The climate and vegetation were not the only elements to have changed – language too. In the lower lands everyone spoke French, but as we reached Ngu and started to climb, more and more people greeted me in English, so that by the time I reached the top I switched to saying “Hello” and “Good Morning” rather than “Bonjour” and “Cava”. The North West Province is English-speaking which made conversing much easier. Ndu was definitely a British colonial town with tea houses and many other colonial influences. The region, like the southern half of the country, is strongly Christian and different churches appear to compete for patrons; in particular Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics and Evangelists. In Ndu we stayed in the Baptist Mission on recommendation from Martin (our guide in northern Cameroon). In many places throughout Cameroon we’ve stayed in different missions (Catholic, Baptist and Presbyterian) and they all provide cheap, clean, secure accommodation. Ndu was no exception. We learned a lot about the region from David who through his good will is giving ‘a leg up’ to many local organisations, providing furniture for the local schools and helping small businesses organise themselves into cooperatives to have a voice and more selling power.

Cycling to the capital of the region, Bamenda requires a strong constitution – there are continuous steep climbs and bulldust is so bad on the descents that at times I had to walk the bike down to avoid further accidents. When I could afford to lift my eyes away from just ahead of my front wheel, the scenery was superb, but most of the time, all concentration was on the road. Such roads turn to mud in the rain. A lack of infrastructure is really holding back the region, whereas with sealed roads they would be struggling to hold back the tourists.

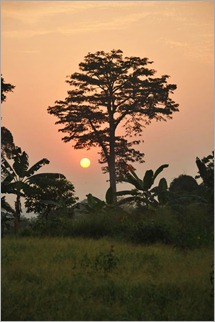

Bamenda is one of the better towns we have visited too. On an afternoon off, Zdenek and I found the “Beverley Hills Cafe and Bar” for lunch. From Bamenda it was tarmac all the way through French-speaking Bafoussam and eventually down, down, down to virtually sea level and 100% humidity, 32 degrees Celsius. We spent an incredibly humid night camping beside a pineapple field, well secluded from the road. The farm workers were a little surprised to find us when they turned up for work – but they were very friendly. The pineapples were being cut and packed for export to France. They were to be transported a few hours after being picked to be potentially on French supermarket shelves the next day! The wet tropical climate and rich volcanic soil means that anything grows. On the flatter land near the coast I passed huge plantations of rubber trees, bananas, papayas, pawpaw, and palm trees.

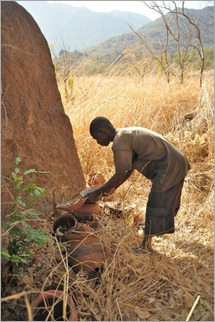

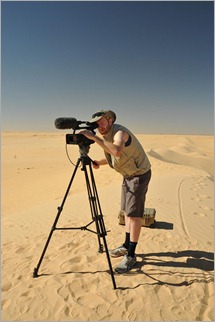

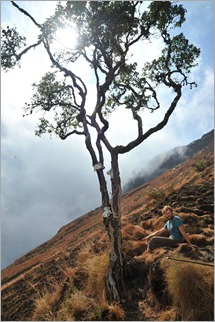

About 15km from the capital Douala we diverted to the town of Buea, the first British capital, at the foot of Mt Cameroon. Climbing this 4090m active volcano, the highest peak in West Africa was a two day break for me off the bike and a great team activity – something we could all do together. It wasn’t exactly a rest though. At the mission where we stayed we met a young New Zealander Charlie, who was travelling independently. We invited Charlie to join us for the trek. The climb started at about 1000m elevation, ascending through jungle to Hut 1 (approx 1900m). Humidity was so high that I was able to wring out my clothes during the first short break. Peter, our guide showed how they collect coco yams, one of their staple root vegetables. There were some amazing fig trees beside the well-trodden track. About half an hour’s climb from Hut 1 the forest ended quite abruptly and we entered the savannah zone – much cooler and drier. Soon above the clouds, we made an incredibly steep ascent over the tufty grasses and black volcanic rubble.  We reached Hut 2 (2860m), our overnight campsite at about 4pm, so there was time to relax and explore the area. The few trees which clung on to the rugged slopes were gnarled and twisted, sculpted by the harsh weather conditions. Our exposed campsite was superb as we could see Buea almost 2000m below on the clear, cold night. The air thinned out as we ascended the last 1300m to the summit the next morning. The volcano last erupted in the year 2000 and Peter pointed out some small trails of smoke rising from the ‘hot’ area. The mountain has also been identified as a biodiversity hotspot, the alpine region being the third in a unique climatic zone. Reaching the summit we were rewarded with vast views of the mountain high above the clouds.

We reached Hut 2 (2860m), our overnight campsite at about 4pm, so there was time to relax and explore the area. The few trees which clung on to the rugged slopes were gnarled and twisted, sculpted by the harsh weather conditions. Our exposed campsite was superb as we could see Buea almost 2000m below on the clear, cold night. The air thinned out as we ascended the last 1300m to the summit the next morning. The volcano last erupted in the year 2000 and Peter pointed out some small trails of smoke rising from the ‘hot’ area. The mountain has also been identified as a biodiversity hotspot, the alpine region being the third in a unique climatic zone. Reaching the summit we were rewarded with vast views of the mountain high above the clouds.

Now for the hard part for me – descending. I am good at climbing which uses similar muscles to cycling, but descending uses a completely different set of muscle actions and is terrible for my injured knee. I descended very slowly and carefully. Much of the path was littered with round balls of solidified lava the size of golf and tennis balls. These stones tend to roll underfoot and make descending hazardous.

A few days after we left the annual “Race of Hope” was held where amazing athletes run to the summit and back. Starting in the town, the men cover the 40km in about four and a half hours! I have no idea how they can descend at speed down these surfaces. A few athletes passed us as we came down, making final preparations for the race – incredibly sure-footed and confident.

We left Dan in Buea to have a few days break there and in Limbe on the coast. John, Zdenek and I returned to the main road and spent two days getting to Yaounde. Negotiating Douala, the economic capital and major port city in Cameroon, was a little hairy and I had to keep my wits about me. The highway between the two big cities was very busy and with good surfaces, vehicle travel at breakneck speeds. The road toll is horrific on this road.

We camped well off the road under a palm plantation. Much of the forest in this region has been or is being cleared to make way for palm trees for making palm oil. We spoke to a worker who explained that a French businessman owned this one, while the Chinese were buying up big tracts of forest to turn into palm plantations. It seems a big, unsustainable sacrifice of rainforest to produce relatively small amounts of oil per hectare.

By the time we arrived in Yaounde at the headquarters of Sundance Resources (who are kindly allowing us to stay and base ourselves there for a decent pit stop), I was exhausted, filthy and very sore from 15 days in a row of mountains and now humidity. We’ve now been on the road for four months and still on track. Yaounde is a time to catch up and prepare for the journey ahead so we are thankful to Robin Longley, Jeff Duff and the team for supporting us. Next stop – a visit to the Plan projects in Bertoua.

{ 5 comments }