Title: Niamey to Maradi

Dates: 27th Dec – 1st Jan 2010 GPS:

Distance: 695km Total Distance: 4828km

Weather: serious headwinds, very dry and dusty

The old song, “I want a Hippopotamus for Christmas” seems a bit excessive in the world’s poorest country, but on Christmas Day, we were taken to at least see the hippopotamus in the Niger River, less than an hour’s drive north of Niamey. Christmas isn’t really big in Niger (being an Islamic country) and after speaking to all my main family members, I hadn’t any major expectations. Here we are being looked after by Australian mining company, NGM Resources, and in particular by their ‘man on the ground’, Ali – or “Super-Ali” as we now refer to him. There doesn’t seem to be a problem Ali can’t fix, or a person in Niger he doesn’t know. Anyway, on Christmas afternoon we were taken out on small pirogues to see three hippopotamus basking in the middle of the fast flowing Niger River, the third largest river in Africa. Our mode of transport seemed rather flimsy when we spotted the enormous animals (I forget just how much they typically weigh, but I would think a tonne would seem right). Hippos are responsible for killing more people than any other animal in Africa, so I was relieved that our guides did not let us drift too close. Afterwards, chicken and chips seemed a reasonable substitute for Christmas turkey.

A little background on Niger: the world’s poorest country seems to bottom out on most indicator tables; education, health and economic development are below Mali and Burkina Faso which rival Niger for this unfortunate distinction. There are approximately 15 million people, the population growing by 3.4% annually. Rural women bear an average of 7.1 children, the highest rate in the world. Sixty percent of people live on less than a US dollar a day. There is less than 20% literacy. Niger is four fifths desert; most of the population live in the Sahelian southern strip of the country which borders with Nigeria. Mostly nomadic cultures live in the desert regions. My plan is to follow the populated region from Niamey to Diffa near Lake Chad in the east, continuing to concentrate on the Sahel.

When researching the expedition I learned about an incredible agricultural-forestry initiative which has slowly been transforming many regions in rural Niger for 30 years called Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR). Niger seems such an unlikely setting for what has now been acknowledged as one of the world’s top 19 most significant agricultural innovations ever. I very much wanted to learn more about FMNR and highlight this success story. In Niamey I looked up (with Ali’s help) Professor Yamba Boubacar, who has been an instrumental figure in educating the rural population (most of whom are illiterate) about the process and virtues of FMNR, developing and streamlining the procedure. We learned that in the region where we were heading, between Galmi, Maradi and Zinder approximately five million hectares of marginal farmland, which by the mid-seventies had been reduced to a windswept, infertile desert, had been restored, the desertification process reversed and livelihoods improved. As I have traversed Senegal, Mauritania, Mali and Burkina Faso I have been struck by the dreadful state most of the Sahelian land is in due to population pressure, over grazing and poor land management practices. FMNR is also being instigated in these other Sahelian countries but from what I understand, Niger seems to be taking the lead.

For two weeks from Niamey, through the Sahel region to Zinder, and then on a week-long excursion into the Sahara Desert where we will visit the Termit region, we have been joined by documentary filmmaker, Stuart Kershaw, who has come to film a promotional video for our documentary. Stuart’s enthusiasm, professionalism and expertise has really spurred the team on and it is a pleasure having him with us.

Niamey to Maradi was a long slog into the Harmattan winds – the seasonal trade winds that prevail from the north east, filling the atmosphere with dust. I put in some very long days just to make the distances planned. I wanted to make the most on Stuart’s time with us. The first two days, 290km to Dogondoutchi was fairly unremarkable. The road, funded by international donors such as the European Union, was some of the best quality we have come across on the journey so far and belies the economic condition of the country. Much aid has been pumped into infrastructure. I passed through small villages regularly with square mud houses and thatched granaries. The road is also flanked by a single power line which runs all the way to the Nigerian border. Nigeria supplies Niamey and in fact Niger with power, so if relations fail, Nigeria can turn off Niger’s power at the flick of a switch. On 22nd December, the president’s second and what should be his final term was up. He has been in power for 10 years, but does not wish to step down. Instead he has implemented a reform so he can stay in office. This impasse has been condemned by the international community. The UN, US and European Union have withdrawn aid to put pressure on the president. Political instability could really hurt the country which I can see is trying very hard to drag itself out of the mire.

Trees had given me some shelter from the wind for the first 300km but after Dogondoutchi I faced wide open expanses and seriously strong headwinds. Daniel decided he was ready to give cycling another go, but after about 25km, the pain in his knee was intense and he was forced to stop. We are all very worried about Dan’s knee. In major towns like Konni and smaller villages I noticed the Nigerian influence. Much trade creeps over the border, at times just a few kilometres away. Fuel is significantly cheaper in Nigeria and much is sold on the black market. In Niger, a litre of diesel costs about $AUD1.30, Burkina $1.80 and Nigeria about $0.80. All the way to Maradi, the headwinds really affected my progress, knocking me down to 13km/hr at times.

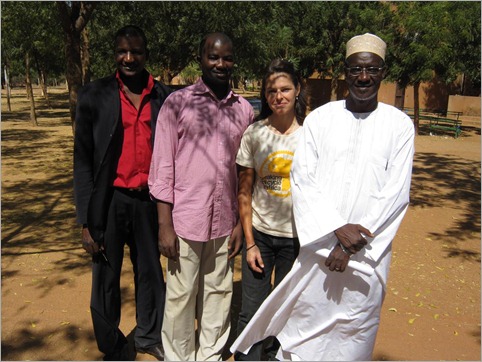

We arrived in Maradi, the third largest city in Niger and commercial capital on New Year’s Day. I had arranged to meet and stay with Sally and Peter Cunningham in Maradi, who have been living and working in the region for SIM (Serving in Mission) for ten years. Specialising in FMNR and associated agro-forestry initiatives, they arranged for us to visit a village which has fully embraced FMNR practices. Our time spent with the Cunninghams, accompanied by Niger radio personality (and FMNR activist) Jano and our interpreter in the village of Djido, 25km SE of Maradi was one of the most important and interesting afternoons of the expedition so far. This is all about communities taking charge of their own destinies – FMNR is a sustainable, low cost practice which makes communities more resilient to drought and other natural and economic threats while allowing them a better quality of life.

We arrived in Maradi, the third largest city in Niger and commercial capital on New Year’s Day. I had arranged to meet and stay with Sally and Peter Cunningham in Maradi, who have been living and working in the region for SIM (Serving in Mission) for ten years. Specialising in FMNR and associated agro-forestry initiatives, they arranged for us to visit a village which has fully embraced FMNR practices. Our time spent with the Cunninghams, accompanied by Niger radio personality (and FMNR activist) Jano and our interpreter in the village of Djido, 25km SE of Maradi was one of the most important and interesting afternoons of the expedition so far. This is all about communities taking charge of their own destinies – FMNR is a sustainable, low cost practice which makes communities more resilient to drought and other natural and economic threats while allowing them a better quality of life.

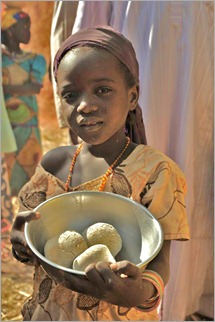

We first met in the centre of the village. Once the elders and village leaders finished their Friday prayers we received an official welcome. After I was introduced by Jano, I was asked to speak and introduce the team. I felt honoured by the reception. This kind of welcome, including a special lunch, would not normally happen everyday, however stakeholders in the FMNR initiative (such as SIM, World Vision, Care International) have been fostering a relationship over a number of years, developing trust and friendships. The villagers’ quality of life has improved and overall they seem happy and extremely motivated.

So what is FMNR? Our little party along with a selection of villagers who were to demonstrate the procedure relocated to a field near the village. Jano gave the first demonstration. The trigger for this farmer-led transformation of the landscape stemmed from an ecological and humanitarian crisis in the 1970’s that threatened the lives of millions and undermined the ability of Niger to sustain itself. Land clearing and tree felling became very common in the 1930’s thanks to the French colonial government who drained the country of its land resources by pushing farmers to grow export crops and providing farmers with disincentives to care for the land. A new law was passed transferring tree ownership to the government and Nigeriens had to purchase permits to use them as they traditionally needed (a process which had been sustainable previously). The French at the same time improved the health care system resulting in higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality. The increased population and lower productivity of the land strained resources and left people vulnerable to famine and natural disasters. Post colonial governments in the 1960’s and 70’s continued to implement this tree ownership law. Positive steps were made after the 4-year famine from 1969-73, firstly by NGO’s (as mentioned) and the Maradi Integrated Development Project, eventually resulting in the change of the law assigning the ownership of trees to the property owners; a long process finally implemented in 1998. This is part one of the big change. People, once educated about the law, take responsibility for their own trees.

So what is FMNR? Our little party along with a selection of villagers who were to demonstrate the procedure relocated to a field near the village. Jano gave the first demonstration. The trigger for this farmer-led transformation of the landscape stemmed from an ecological and humanitarian crisis in the 1970’s that threatened the lives of millions and undermined the ability of Niger to sustain itself. Land clearing and tree felling became very common in the 1930’s thanks to the French colonial government who drained the country of its land resources by pushing farmers to grow export crops and providing farmers with disincentives to care for the land. A new law was passed transferring tree ownership to the government and Nigeriens had to purchase permits to use them as they traditionally needed (a process which had been sustainable previously). The French at the same time improved the health care system resulting in higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality. The increased population and lower productivity of the land strained resources and left people vulnerable to famine and natural disasters. Post colonial governments in the 1960’s and 70’s continued to implement this tree ownership law. Positive steps were made after the 4-year famine from 1969-73, firstly by NGO’s (as mentioned) and the Maradi Integrated Development Project, eventually resulting in the change of the law assigning the ownership of trees to the property owners; a long process finally implemented in 1998. This is part one of the big change. People, once educated about the law, take responsibility for their own trees.

Trees that have been clear felled are cut off at the stumps, leaving the roots intact and ready to re-sprout. These root systems are often referred to as “underground forests”. Jano theatrically demonstrated the simple process. The bush which had sprouted from the roots had many stems. FMNR simply involves pruning away the lesser branches, leaving usually the four most robust ones. The stems are also cleaned of side branches and runner roots are cut. This encourages the nutrients to be channelled into growing four strong trunks and the trees are trained to grow taller. Then if the owner needs to cut a trunk for firewood or use as building material for example, they can extract one of the stems and still have two or three trunks to use later. In times of hardship they may even take the whole tree, but with whatever is taken, not even a leaf is wasted. Where FMNR is fully established, villagers typically grow about 200 trees per hectare. This process improves soil fertility, providing wind breaks to counter soil erosion, trees (acacias) fix nitrogen in the soil, leaves provide mulch, crop yields improve, pods and leaves provide fodder in the dry season, local species of plants and animals return. Trees provide shelter for the animals. Villagers can sell firewood and have an income – they can normally only provide enough food for 8 months of the year and typically the men have had to leave the village to find work to keep their families for the remaining four months. Now they can stay and contribute to the village economy. Women no longer have to spend hours collecting firewood every day (they used to average 2.5 hours a day) and can use the time productively to farm trees and grow food. This has improved their social status. When the land was subjected to wind erosion, farmers had to regularly reseed their millet and sorghum crops several times to grow one crop. With added protection from trees they need only sow once, saving time and money. Surpluses are sold off. In fact trees are now referred to as their “banks”. Rather than putting money in a savings bank, when a villager needs funds they can simply draw on their wood surplus. With climate change decreasing the reliability of the weather in a region which is characterised by a marginal climate, FMNR is immensely important for the future. With added productivity, farmers are developing export markets, mostly with Nigeria, reversing the general trend.

It is difficult to see any negatives from FMNR. After Jano explained and demonstrated the process it was the men’s turn to give testimonies of how the initiative has changed their lives; then the women explained the benefits they have received, also demonstrating their expertise.

Peter has also been instrumental in introducing and developing the Australian wattle and other acacia varieties with great success. This has evolved from an interesting exchange between two Aboriginal women from Yuendumu (near Alice Springs, Northern Territory) and locals from Maradi.

We learned a lot in an afternoon. On the way back we stopped off to inspect land which has not been involved in FMNR – barren sandy windswept soil. Nothing was growing apart from a few skeletal trees.

Back at Sally and Peter’s place we were treated to some magnificent home cooking – a little Australian sanctuary in the middle of Niger was a most welcome departure. The Cunninghams are about to return to Hamilton, Victoria later this year, which will be a big culture shock after ten years. Peter mentioned that he saw Niger’s biggest challenge now is to stem population growth. While the national figures cite that each woman has 7.1 children, Ruth, another SIM worker who joined us and who has lived in Niger for 20 years says that in this region it is more like 8-10 children. Peter knows a man who has 38 children! A population explosion has already happened in the last five years, so in a few years from now there will be a whole new generation with little to do and the pressure on the land mounting once again. I think this new found wealth (relative) from FMNR needs to go a step further and funds need to be directed towards education. Educating 15 million people in time will be a challenge, but easier than educating 25 million people in 2020. I hope the success of the FMNR initiative and the manner in which the messages have been spread from farmer to farmer, village to village may somehow occur with education with a similar model.

Back at Sally and Peter’s place we were treated to some magnificent home cooking – a little Australian sanctuary in the middle of Niger was a most welcome departure. The Cunninghams are about to return to Hamilton, Victoria later this year, which will be a big culture shock after ten years. Peter mentioned that he saw Niger’s biggest challenge now is to stem population growth. While the national figures cite that each woman has 7.1 children, Ruth, another SIM worker who joined us and who has lived in Niger for 20 years says that in this region it is more like 8-10 children. Peter knows a man who has 38 children! A population explosion has already happened in the last five years, so in a few years from now there will be a whole new generation with little to do and the pressure on the land mounting once again. I think this new found wealth (relative) from FMNR needs to go a step further and funds need to be directed towards education. Educating 15 million people in time will be a challenge, but easier than educating 25 million people in 2020. I hope the success of the FMNR initiative and the manner in which the messages have been spread from farmer to farmer, village to village may somehow occur with education with a similar model.

The cycling journey will resume from Maradi in a week’s time. From Maradi we are travelling out to the Sahara Desert with John’s special Touareg contacts, Limane and Mamane from the Agadez-based company Tidene. This will give my body time to rest ready for the next big stage across to eastern Niger, into Nigeria and through Cameroon while getting a firsthand experience of the pure sands of the Sahara, the beauty of the Termit region, a remote UNESCO World Heritage Site, and an insight into the culture of the nomadic Tubu people, reportedly the group of people most specifically adapted to the harsh desert.

Incidentally, Stuart has been very busy shooting great range of footage for the promotional video. He has also edited some great little pieces which we will soon be able to show you on this site.

{ 1 comment }