Title: Ouagadougou to Niamey

Dates: 18th to 23rd Dec GPS:

Distance: 575 km Total Distance: 4133 km

Roads: 495km tarmac; 80km gravel, sand

Weather: mid’s 30’s during the day, cooler evenings, constant east-NE headwinds

My first impressions of Burkina Faso were the friendly, slightly more understated and reserved nature of the people we met in the towns and villages as we passed through. People greeted us with a two-handed wave (rather than the usual single hand wave) which is rather difficult to reciprocate from over the handlebars! They generally seemed happy and content. Even though there is obvious poverty – Burkina is rated as the second poorest country in the world – there seemed to be construction of new roads and buildings going on just about everywhere. Burkina has benefitted from political stability since their government was democratically elected in 1987. They were one of the first Sub-Saharan countries to prepare their Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper which qualifies them for debt relief. This means they have an effective donor coordination strategy and an environment more conducive to foreign investors. In Ouagadougou we were guests of one of our sponsors, Gryphon Minerals, who themselves have been attracted by the stable economic conditions and the prospect of mining gold tenements in the Banfora region in the south west of the country. A big thank you goes to Isabelle Guirma, Pascal, Alice and Martin who took care of us in Ouagadougou.

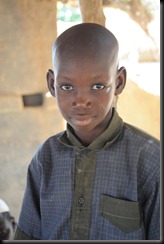

My main focus however in Burkina Faso was to look at the state of women’s and girls’ education by visiting one of Plan International’s projects in the Samentenga region approximately 100km to the north east of the capital. Traditionally in Burkina, as with most of the Sahelian countries, boys have been given priority for education – girls are expected to work, marry at an extremely young age and produce a large family. The country also sits at the bottom of the table as far as illiteracy is concerned. In 2007, 29% of adults over 15 years are able to read and write. As I discovered, some very promising sustainable changes are being made, particularly cultural changes.

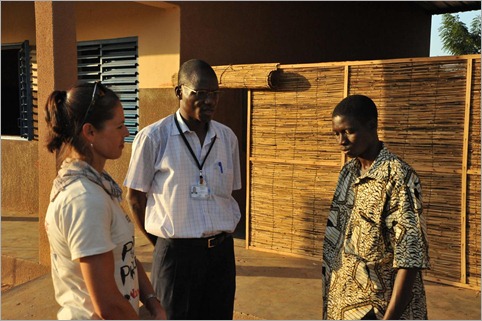

Plan International of Australia connected me with Plan Burkina and our visit was hosted by Ms Francoise Kabore and the director, Mr Oumarou Koala (And yes, we had the obligatory joke about the relevance of the director’s name to Australia). Once in Kaya, the regional capital, the three of us and a cameraman drove out to a small village where I was to be shown the new BRIGHT school. (John and Dan had stayed back in Ouagadougou to collect our visas which had needed to be extended. Paddy has gone home to Australia for Christmas.) BRIGHT stands for Burkinabe Response to Improve Girls’ Chances to Succeed. The project was initially set up by a US organisation called the Millennium Challenge Corporation. Launched in 2006, Plan International is the major stakeholder. Since then 132 BRIGHT schools have been built educating over 17,000 new primary students; more than half of which are girls.

We arrived outside the school to find many of the villagers waiting to greet us. Mr Koala asked for permission from the community before we could take photos. We all introduced ourselves; Francoise translating for me. After formalities were over and we were accepted, the elders selected a group containing a representative cross section of the community to meet, answer my questions and discuss their thoughts about education and how it affects their lives. Women with their babies, elders and community members of all ages filled the largest of three classrooms. Francoise, Oumarou and I sat out the front. Here’s a summary of what we discussed:

How has the village changed in the three years since the school was built? What was it like before?

‘The school brings the community together; it gives hope for the future. Now our children have opportunities which we never had.’

One of the more outspoken men explained that he had never had the chance of education – he can’t read or write (but I complemented him on his ability to speak – he was very articulate). He said now girls are no longer expected to marry and have children when they are very young. Now they are encouraged to go to school for formal and non-formal classes. This is a big change. More girls than boys attend school here and their results are marginally better overall. (Hearing the man explain this new attitude really touched me – this is such an important cultural change)

One of the more outspoken men explained that he had never had the chance of education – he can’t read or write (but I complemented him on his ability to speak – he was very articulate). He said now girls are no longer expected to marry and have children when they are very young. Now they are encouraged to go to school for formal and non-formal classes. This is a big change. More girls than boys attend school here and their results are marginally better overall. (Hearing the man explain this new attitude really touched me – this is such an important cultural change)

How have they encouraged more girls to attend school?

Initially partners of the BRIGHT Project educated the community leaders who in turn individually spoke to each family to explain the importance of attending school. School lunches were provided for those who attend as incentive. These people are very poor and this ensures the kids get at a good meal every day.

(To the three teachers) What can be done to improve the quality of their work? What do they need? The young headmaster read out the class sizes – average of 55 students per class. Currently there are three classrooms and teachers are expected to teach two years. Their dream would be to have a classroom for each year level. Another request was really simple – ‘We need electricity so the school can have light.’ Teachers are restricted to daylight hours to prepare lessons. If there were lights, the school could then be the focus for community event after dark and students could also do their homework. A normal school day would entail starting at 7.30am, working through to lunch (I think this was 11.30am). Then they break before resuming at 3pm for the two hour afternoon session.

What are the main types of non-formal education?

There is a special program for young mothers to improve literacy as well as give practical lessons such as in agriculture. With young better educated mothers, this ensures their children have the support and encouragement they need to attend school every day.

There is a special program for young mothers to improve literacy as well as give practical lessons such as in agriculture. With young better educated mothers, this ensures their children have the support and encouragement they need to attend school every day.

(To the women) What changes and improvements would you like to see in the village over the next five years?

Water is the main issue. The village only has one well and there is just enough water for drinking (not growing things). A man who had walked from a neighbouring village said that often young girls don’t arrive at school until about 10.30am because they have to queue to collect water, then carry it some distance. Here they can only grow millet (like in much of the Sahel) because it does well in dry conditions and only has a four month growing cycle.

Another woman piped up to say that the other outstanding need is a health centre. Now they have to walk many kilometres to get medical help. She said education is good for preventing health issues, including delaying child birth until the mothers are older (and their frames ready for pregnancy and birth), but they need a health centre.

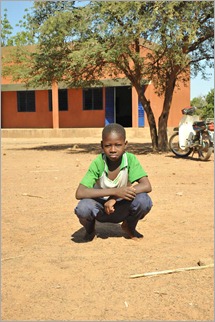

These were the main topics we discussed. We took plenty of photos after which the teachers introduced me to their students. This visit has given me much more insight into how the whole community is affected by the new school. The community is obviously very poor, but the spirit is so positive and their ideas constructive. I think, as was mentioned initially, the community is inspired by the progress made since 2006.

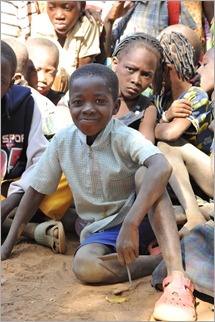

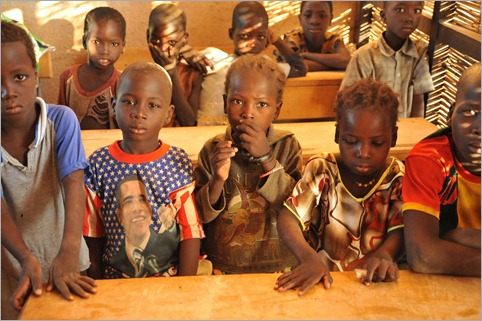

John and Daniel arrived in the early evening with visas and joined me the following morning when Francoise and Oumarou took us to another larger village to be a part of a special educational gathering being presented by a group of senior students from the secondary school. Hundreds of kids of all ages, the teachers and a few others gathered around where the young leaders were to perform and deliver their messages. Facilitated by Plan Burkina, this was designed to be a fun way to get important messages across and was a great example of child-centred development. The main message of the day was to stop violence in schools. A group of approximately twelve students, each having a few lines to say, delivered the messages, starting with (roughly) “Education is a basic human right, everyone has the right to receive an education”… If students are afraid to go to school because of violence, then this affects their learning, health, the community… On the backs of their t-shirts I could see important messages about stopping violence, dental health and education. After the main messages were performed (and this was really well done), the students invited first their teachers to individually join them the dance a little. Next there was a question and answer session where students from the audience, primary and secondary levels were asked questions. If they gave the right answer they received a little gift. At times the gift giving got a little out of control with over-enthusiastic kids and the teachers had to calm the audience down. More dancing. The second time round we all in turn were invited up – even I had to take part! To finish Mr Koala rounded everything up, also introducing me and the expedition in two languages (French and then Mossi, the local language). I was invited to say a few words which he translated.

After it was all over, I met the English teacher, Zongo Karime and encouraged him to get involved in the BTC education program. He would like to but obtaining access to the internet is difficult and expensive for him. Zongo also explained how difficult it was for him to work in the secondary school. There is effectively only one decent classroom and he has to teach classes of 130 children! Not surprisingly, he said he is burnt out. We had lunch with the teachers before saying goodbye to Francoise and Oumarou, two very impressive people, and moved on.

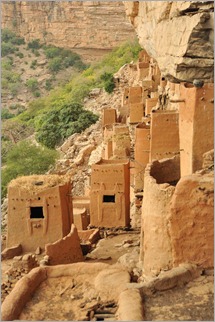

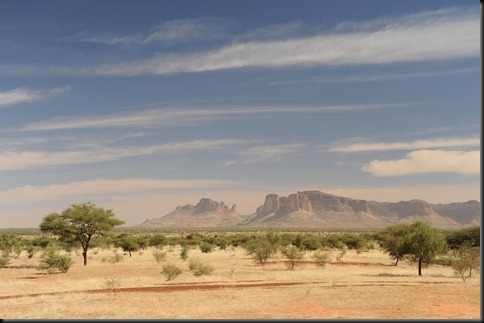

The region around Kaya is quite attractive, with a few ancient rocky hills – good for camping. The road to Dori was obviously brand new with regular small villages along it. I pushed on into a steady headwind as usual. Dan’s knee isn’t right yet, so he’s manning the camera. Bani is a town of note with seven small mosque ruins built on the hill overlooking the village. It was obvious that as we headed north the people, land and climate were changing. We were back into an Islamic dominated region, whereas around Ouagadougou it was mostly Christian.

The 90km route from Dori (Burkina Faso) to Tera (Niger) crossed a little-used border. We had major difficulties even finding the track out of Dori. We were told by a couple of people to follow a good gravel road towards Sebba, then there would be a sign and we should turn left after about 4km. I set off leaving John and Dan to refill and filter our water containers, cycled past the 4km sign and thought the directions must be wrong. I asked a couple of people and they sent me back to town. At the turn off I met Dan and John heading in the same direction and so we asked a few more people – all of whom all sent us down the same road. This time I’d done 6km down the Sebba road only to have to turn around again. A motorcyclist eventually set us on the right path, 4km from town. No wonder we missed it. The sign was about something completely different, not a road sign, and the inconspicuous track was marked with a small piece of tape! I’d added another 15km for nothing. Not quite what we expected for a road leading to a border crossing! The track was sandy at times, and like back on the Mauritania-Mali border, there were no road signs. It was just a case of cycling from village to village asking for directions to the village of Sitenga on the border. As these people rarely see white people, if I did stop to ask for directions the whole village would appear and it was difficult to explain that I had to keep moving on to get to Tera. This little section was another highlight.

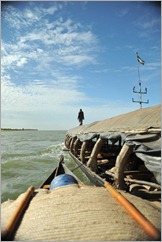

Times are about to change in this region though. A brand new road is being pushed through – on the Niger side, 40km from Tera, the newly metalled road starts. Much of it is still under construction, forbidden for vehicles to use it yet, but they didn’t seem to mind me creeping quietly over the new surface. I did another huge 100-mile day into the wind to get within reach of Niamey, Niger’s capital. At Farie we crossed the River Niger at dusk. John got there a little before me and was able to put the Land Rover on the boat, which only crosses when it is full. Dan waited behind for me. Eventually Dan and I took a pirogue across the river at last light. Ali, our main contact and fixer from another sponsor, NGM Resources, was waiting for us at Farie. There was little there, certainly no place to stay, so Ali led us down to Niamey where we have some very comfortable accommodation. The following morning we drove back to Farie and I cycled the final 60km, this time into a cruel headwind. John and Dan accompanied me for about 20km each; Dan just testing out his knee. John likes to get on the bike when possible to get some exercise – and it’s good to have his company.

So it’s Niamey for Christmas. Ali just arranged for us to see the wild giraffes about 70km south of the city. There are about 200 which co-exist with villagers in the region. Apart from a few monkeys and vultures, the giraffes are the first wildlife we’ve really seen. Over the years, the human population has grown to levels unsustainable in the Sahel and the loss of habitat has pushed out most of the wild animals.

{ 5 comments }